TAKE A WALK DOWN MEMORY LANE

Storytelling Project

Here's a little about our new project:

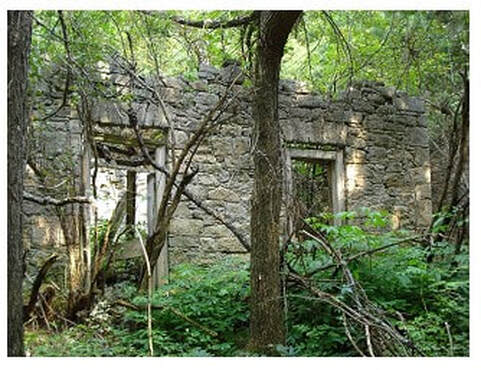

The Middleville and District Museum has launched a project that will record a collection of memories of days gone by. Preserving stories from the one room schoolhouse experience is a natural venture for the Museum that saw its beginnings in the beautiful 1861 Middleville stone schoolhouse.

The Museum is hoping to hear from former students who have memories of attending a rural one room schoolhouse anywhere. Recalling the experiences of having multiple grades in the same classroom with one teacher, stoking the woodstove to heat up a hot lunch, braving the cold on a trip to the outhouse or climbing a tree in the schoolyard inspires a flood of memories.

The Museum is inviting the public to share their stories and join us in preserving them for future generations to enjoy. We are also eager to hear other stories of a time before the establishment of the modern conveniences we enjoy today.

Harnessing up a favourite driving horse for a spin through the countryside in the buggy or cutter paints a picture of a pleasant afternoon. Community picnics at a local landmark, a day of fishing on the Floating Bridge, showing prize livestock at the local fair and a bumpy ride in a Model T all bring a smile to the face of those who have lived through many changes in their lifetime. If you have stories to share, please let us know. If you know of someone who has stories to share, please let them know about our project and encourage them to contact us.

The Museum is hoping to hear from former students who have memories of attending a rural one room schoolhouse anywhere. Recalling the experiences of having multiple grades in the same classroom with one teacher, stoking the woodstove to heat up a hot lunch, braving the cold on a trip to the outhouse or climbing a tree in the schoolyard inspires a flood of memories.

The Museum is inviting the public to share their stories and join us in preserving them for future generations to enjoy. We are also eager to hear other stories of a time before the establishment of the modern conveniences we enjoy today.

Harnessing up a favourite driving horse for a spin through the countryside in the buggy or cutter paints a picture of a pleasant afternoon. Community picnics at a local landmark, a day of fishing on the Floating Bridge, showing prize livestock at the local fair and a bumpy ride in a Model T all bring a smile to the face of those who have lived through many changes in their lifetime. If you have stories to share, please let us know. If you know of someone who has stories to share, please let them know about our project and encourage them to contact us.

Please note: We will be videotaping the stories, but storytellers do not have to appear on camera if they would prefer not to do so. We can record the audio alone with a still photo.

If you are interested in participating in our project to capture stories from the past and preserve them for generations to come contact us at [email protected] or by filling in the form below. You can also reach us by visiting our Contact page for more options.

Stories of the past...

The stories you will read below are family stories. They will resonate with many readers who have heard the stories of their ancestors passed down from generation to generation. We hope you enjoy these remarkable testaments to the courage and resiliency of those who broke the trail.

Stories

Memories by Mary Beth Wylie

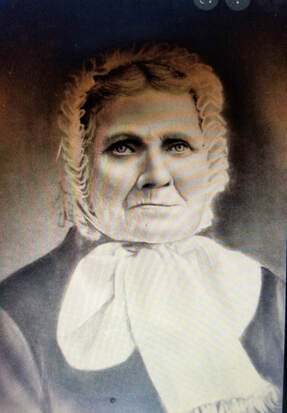

The Story of Maggie Watt Paul

What you discover when you take the time to explore old documents:

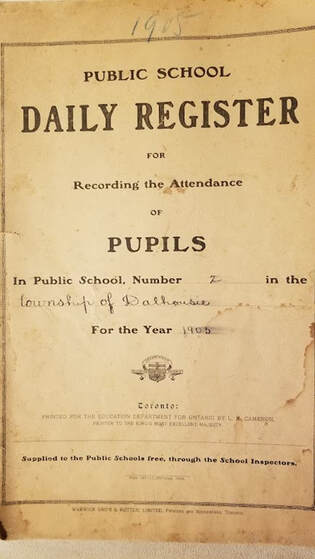

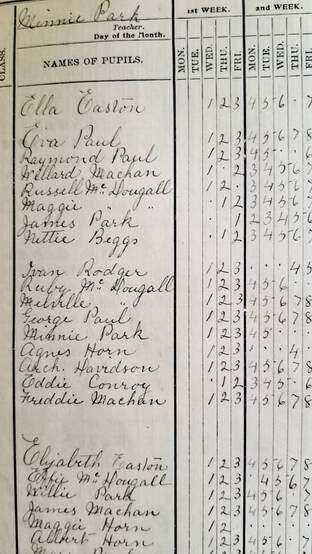

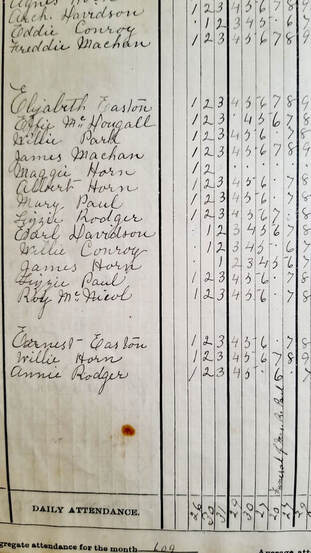

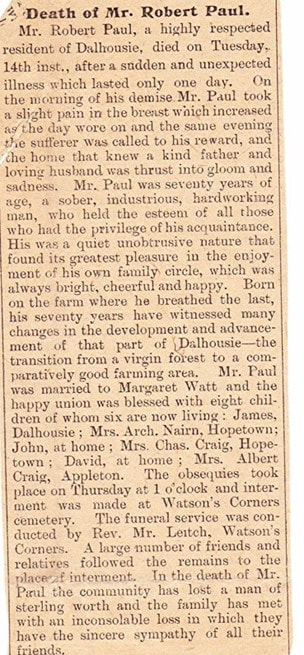

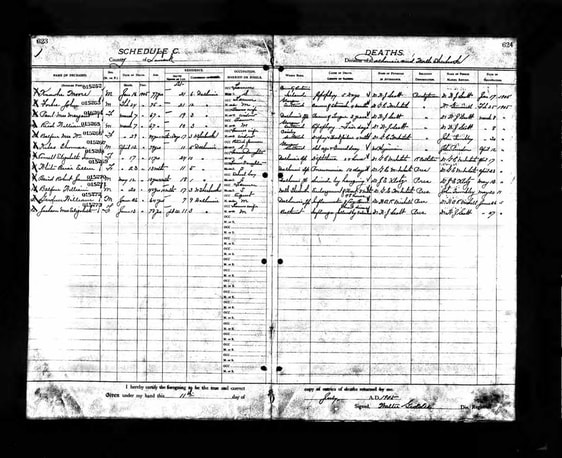

I was lucky to obtain old attendance records from Hoods school dating from 1905 - 1915 (this was the pioneer school at the corner of concession 3 and Sugar Bush Way in Dalhousie). While reading through them I noticed that on March 7 1905, the teacher had documented students were “absent for Mrs. Robert Paul’s funeral”.

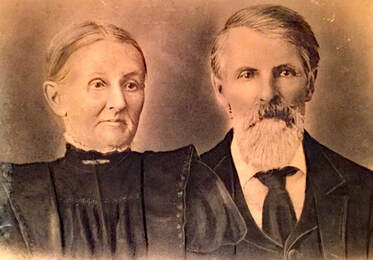

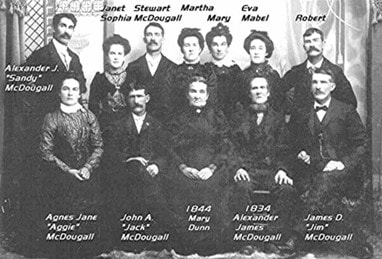

Mrs. Robert Paul was born Margaret “Maggie” Watt and she was my great great grandmother.

In 1837 Maggie was the third of eleven children born to homesteaders Alexander Watt and Euphemia Gibson. Her father had arrived in 1820 from Glasgow and settled on Lot 25 concession 3 in Dalhousie, Lanark County. Following the death of his first wife he married Euphemia Gibson and they remained in Lammermoor in a stone house built by Euphemia’s father, stone mason Robert Gibson.

In 1856, at the age of 19, Maggie married 25 year old Robert Paul (my gg grandfather) and she moved down concession 3 to the west half of lot 21. The lot was shared with Robert’s parents James Paul and Christina Scott.

Within the first year of marriage, she gave birth to my great grandfather James C Paul.

In 1859 her brother-in-law James H Paul married 19 year old Jane Gibson, Maggie’s cousin, and they settled down the road on lot 17.

Her second child Euphemia “Famie” was born in 1859.

Between 1856 and 1880 Robert and Maggie continued to purchase land around their farm and expand their family. Together with her husband and family they slowly turned the homestead log home into a functioning farm.

In the spring of 1881 at the age of 44, Maggie gave birth to her eighth child Margaret Elizabeth “Lizzie”. The 1881 census confirmed all 8 children survived and were living at home.

I am sure it eased the workload to have her brother and sister-in-law James H and Jane Paul living down the road raising their nine children born during that same period. Between the two families there were many cousins and siblings to help on the farms.

Twenty years later, the 1901 Census confirms she was still living on the homestead with her husband Robert and their sons David Montgomery Paul, his wife Sarah Anne (Paul), and John S Paul with his wife Jessie Ann (James).

In March 1905, at the age 68, after suffering for 3 years Grandma Maggie died of cancer of the tongue.

On the day of her funeral, the school noted the absence of the neighbourhood children…some were her grandchildren.

Margaret Watt Paul and Robert Paul are buried in Saint Andrews Cemetery in Watsons Corners.

Just remembering and being grateful for another one of our strong amazing pioneer grandmothers.

I was lucky to obtain old attendance records from Hoods school dating from 1905 - 1915 (this was the pioneer school at the corner of concession 3 and Sugar Bush Way in Dalhousie). While reading through them I noticed that on March 7 1905, the teacher had documented students were “absent for Mrs. Robert Paul’s funeral”.

Mrs. Robert Paul was born Margaret “Maggie” Watt and she was my great great grandmother.

In 1837 Maggie was the third of eleven children born to homesteaders Alexander Watt and Euphemia Gibson. Her father had arrived in 1820 from Glasgow and settled on Lot 25 concession 3 in Dalhousie, Lanark County. Following the death of his first wife he married Euphemia Gibson and they remained in Lammermoor in a stone house built by Euphemia’s father, stone mason Robert Gibson.

In 1856, at the age of 19, Maggie married 25 year old Robert Paul (my gg grandfather) and she moved down concession 3 to the west half of lot 21. The lot was shared with Robert’s parents James Paul and Christina Scott.

Within the first year of marriage, she gave birth to my great grandfather James C Paul.

In 1859 her brother-in-law James H Paul married 19 year old Jane Gibson, Maggie’s cousin, and they settled down the road on lot 17.

Her second child Euphemia “Famie” was born in 1859.

Between 1856 and 1880 Robert and Maggie continued to purchase land around their farm and expand their family. Together with her husband and family they slowly turned the homestead log home into a functioning farm.

In the spring of 1881 at the age of 44, Maggie gave birth to her eighth child Margaret Elizabeth “Lizzie”. The 1881 census confirmed all 8 children survived and were living at home.

I am sure it eased the workload to have her brother and sister-in-law James H and Jane Paul living down the road raising their nine children born during that same period. Between the two families there were many cousins and siblings to help on the farms.

Twenty years later, the 1901 Census confirms she was still living on the homestead with her husband Robert and their sons David Montgomery Paul, his wife Sarah Anne (Paul), and John S Paul with his wife Jessie Ann (James).

In March 1905, at the age 68, after suffering for 3 years Grandma Maggie died of cancer of the tongue.

On the day of her funeral, the school noted the absence of the neighbourhood children…some were her grandchildren.

Margaret Watt Paul and Robert Paul are buried in Saint Andrews Cemetery in Watsons Corners.

Just remembering and being grateful for another one of our strong amazing pioneer grandmothers.

In 1902 Maggie's husband Robert suddenly died of heart failure

In March 1905, at the age 68, after suffering for 3 years Grandma Maggie died of cancer of the tongue.

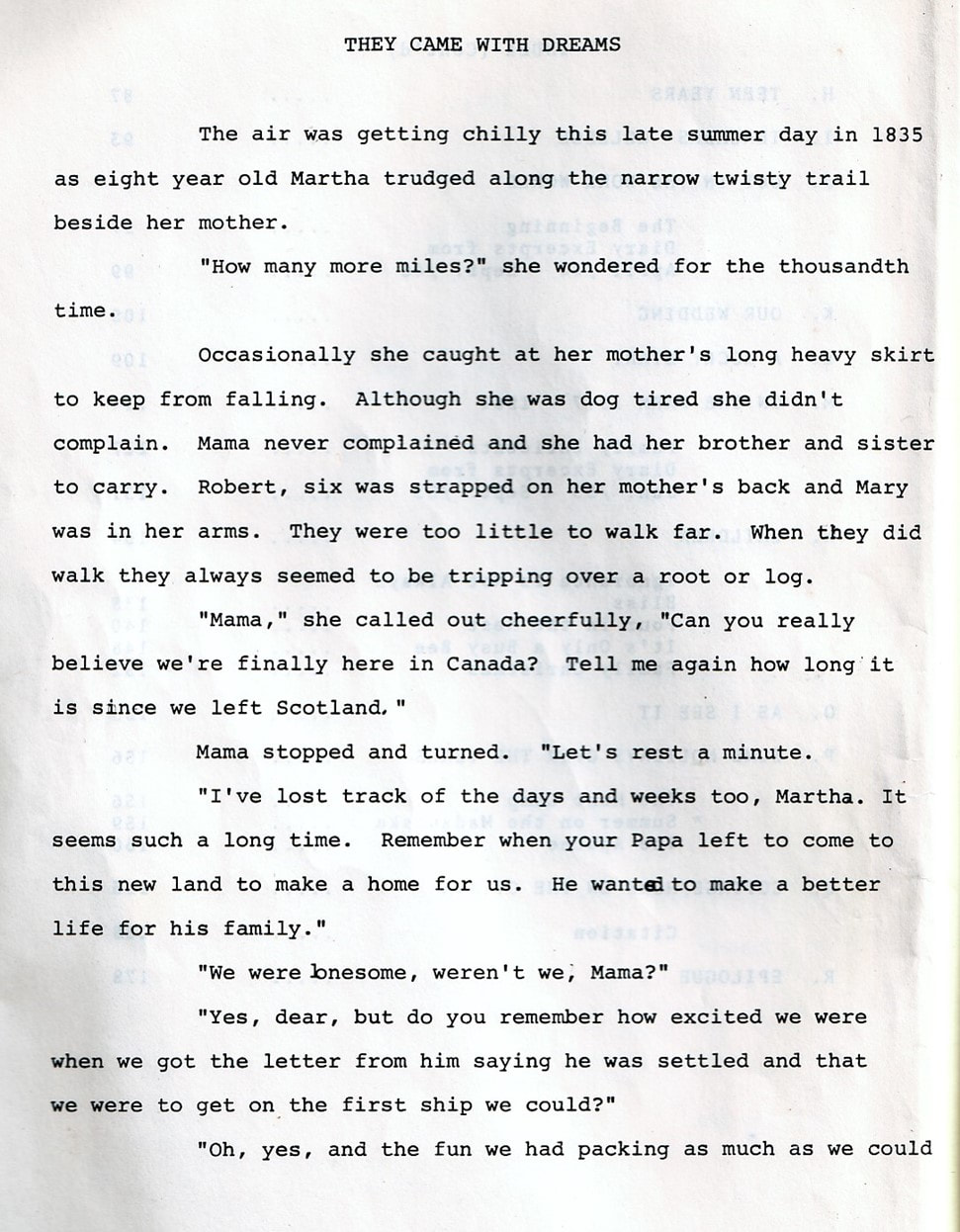

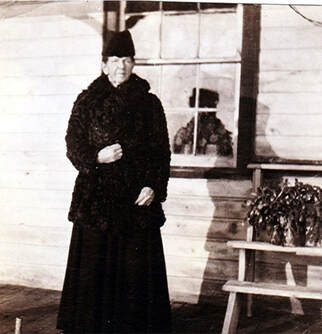

The Story of Martha Dunn

This story of my great, great, great Grandmother was told to me by my mother Eileen Paul Wylie when I was just a child. Little did she know that these people would be as real to me today as my immediate family. This is mom’s story:

Mary Dunn remained in Canada and in 1849 she married James Beith. They had one child together - Isabella.

School Days

School Game Memories of Eileen Paul Wylie (1922-2007)

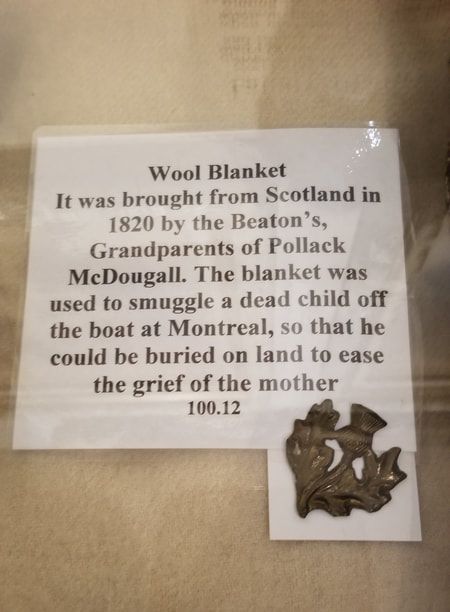

A Blanket Tells a Story

by Mary Beth Wylie

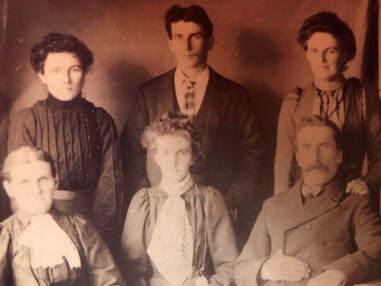

In the Middleville & District Museum, tucked away in a corner of an exhibit, lies a white woolen blanket. It caught my attention because I remembered my grandparent’s friend Pollack McDougall and I was curious about the blanket’s history.

I discovered the blanket belonged to Janet Paton who was “A wee little girl born the 20th day of September of the year 1820 in the Gorbals area of Glasgow, Scotland. The youngest of seven children, she spent the years of her childhood and maidenhood in her native city, marrying there at the age of 19 to John Beaton a widower tailor from the Burgh of Abbey Paisley in Renfrewshire County.

In the space of two years she had two children, George in 1840 and John in 1841 and also a stepson William Pollock Beaton from her husband’s first marriage. Later that year with her husband and three children she boarded the sailing vessel “The Renfrew” and sailed for the wilds of Canada. The voyage was rough and stormy taking seven weeks and three days to make the landing at Quebec City.

Off the coast of Newfoundland the sea was so rough the Captain ordered the hatches to be closed down, and for three days and three nights the five hundred and forty two passengers were imprisoned below deck. To make the voyage even more challenging measles broke out and at least fifteen children succumbed from the disease and were buried at sea. Janet’s infant son John also sickened and died but Janet shrank from consigning her baby to the chilly waters of the sea and nursed him in her arms for several days until their sailing vessel reached the land and the little baby was given a proper burial.”

Excerpt from an article written by Darlene Gerow Jones. Great, Great Grandaughter of Janet Paton Beaton, for the Vernon BC Genealogical Society.

In the space of two years she had two children, George in 1840 and John in 1841 and also a stepson William Pollock Beaton from her husband’s first marriage. Later that year with her husband and three children she boarded the sailing vessel “The Renfrew” and sailed for the wilds of Canada. The voyage was rough and stormy taking seven weeks and three days to make the landing at Quebec City.

Off the coast of Newfoundland the sea was so rough the Captain ordered the hatches to be closed down, and for three days and three nights the five hundred and forty two passengers were imprisoned below deck. To make the voyage even more challenging measles broke out and at least fifteen children succumbed from the disease and were buried at sea. Janet’s infant son John also sickened and died but Janet shrank from consigning her baby to the chilly waters of the sea and nursed him in her arms for several days until their sailing vessel reached the land and the little baby was given a proper burial.”

Excerpt from an article written by Darlene Gerow Jones. Great, Great Grandaughter of Janet Paton Beaton, for the Vernon BC Genealogical Society.

Janet Paton Beaton’s Obituary

The Lanark Era Wednesday October 14 1903

Darling, Tues.Sept.22nd 1903, Janet Beaton, wife of John Beaton. She was born in Glasgow Scotland, 15 Sept.1820 and married there at the age of 19 years. She and her husband and two children emigrated in 1842 to Canada on the ship "Renfrew". During a very stormy voyage, measles broke out on the ship that caused the death of her infant child. She concealed its demise until debarkation in order to insure a burial. Fifteen other children died during the voyage and were consigned to the sea.

After living near Clayton they moved to Darling in 1858 where her husband was a schoolteacher. He died eleven years ago and both were buried in their family plot on the property. They had a family of thirteen of whom nine reached adulthood. There survive three sons and three daughters; George at Kearney, Ontario; Stephen; Margaret (Mrs. Wm. McDougall) of Dalhousie; Elizabeth, widow of the late Gavin Lindsay of Almonte; John of Almonte; and Janet, wife of Rev. W.L. Hendrich of Huntingdon, Mass. In addition there is Henry Gilchrist Beaton a son adopted in 1883. The funeral was held at the homestead Thurs. Sept. 24th.

The Lanark Era Wednesday October 14 1903

Darling, Tues.Sept.22nd 1903, Janet Beaton, wife of John Beaton. She was born in Glasgow Scotland, 15 Sept.1820 and married there at the age of 19 years. She and her husband and two children emigrated in 1842 to Canada on the ship "Renfrew". During a very stormy voyage, measles broke out on the ship that caused the death of her infant child. She concealed its demise until debarkation in order to insure a burial. Fifteen other children died during the voyage and were consigned to the sea.

After living near Clayton they moved to Darling in 1858 where her husband was a schoolteacher. He died eleven years ago and both were buried in their family plot on the property. They had a family of thirteen of whom nine reached adulthood. There survive three sons and three daughters; George at Kearney, Ontario; Stephen; Margaret (Mrs. Wm. McDougall) of Dalhousie; Elizabeth, widow of the late Gavin Lindsay of Almonte; John of Almonte; and Janet, wife of Rev. W.L. Hendrich of Huntingdon, Mass. In addition there is Henry Gilchrist Beaton a son adopted in 1883. The funeral was held at the homestead Thurs. Sept. 24th.

“During excavations at the Omega mines in 1963, several old graves were unearthed, containing the remains of a pioneer family: John Beaton, one of the early teachers and farmers in the area, along with his wife, Janet (Paton), daughter, Helen, son, Thomas, and an unnamed child, who likely died at birth.

The grave marker indicated that the mother, Janet Beaton, was buried in 1903, at the age of 83, so the family were believed to be early settlers to the area. Bob Neilson of Clydesville levelled off the grave at the Omega mine, and the families remains were moved to the Hopetown Cemetery, where a gravestone was erected in their memory.”

Arlene Stafford Wilson – Tatlock Memories

The grave marker indicated that the mother, Janet Beaton, was buried in 1903, at the age of 83, so the family were believed to be early settlers to the area. Bob Neilson of Clydesville levelled off the grave at the Omega mine, and the families remains were moved to the Hopetown Cemetery, where a gravestone was erected in their memory.”

Arlene Stafford Wilson – Tatlock Memories

ONE ROOM SCHOOLHOUSE REFLECTIONS

ROLLO PARK, SASKATCHEWAN

By Robert Burchill

While I probably spent about equal time in the old and new versions of Rollo Park School #5045, when anything reminds me of those days it is always the log building that comes to mind. Perhaps that is because it was my first school, or because I was at a more impressionable age when I attended it. Possibly it is because the log school had a charm that the new one lacked.

The old barrel heater and the tin fire screen around it that became festooned with woolen mitts in winter; the sudden odor of smoldering mitts and socks emanating from it; the long chimney pipe that traversed the room. In comparison, the central heating system of the new building lacked character and utility.

The windows of the new school were deliberately set at a height that let in light, but prevented an easy view of the road. This meant that when a truck or tractor or snowplow went by, everyone had to stand up to catch a glimpse, and the teacher had to shout at everyone to sit down. In the old school, the windows were set for easy scanning of the horizon. You did not have to disrupt proceedings to see whose truck was passing, or that Corky Flannigan was burning fire breaks around his granaries. Today we would call the old building "user friendly".

The desks in the old school were fine instruments for serious pedagogy. Cast-iron frames defined the contours of the gang desks where everyone sat two-by-two, except for a row of small, single beginners' desks on the window side, and a larger row of single, older students' desks on the other. Opening the lid of a two-by-two desk required the agreement of both parties involved, a fact that today would likely be seen as freighting academy with sinister political content. The old desks had a quality of purpose about them that was lacking in the single unit drawer/seat/arm rest/writing top versions that replaced them. In retrospect, the old desks were much more politically correct in that they inconvenienced left- and right-handers equally, whereas their replacements were for right handers, period.

When you entered the old school and turned left, there was a box cupboard on your immediate left with a water pail on top and firewood underneath. A step further and the heater was on your right, while on your left a bench under the window was generally loaded with lunch pails and filled beneath with boots and rubbers. Pegs on the wall in front held outerwear.

Turning right, you went past the three large windows to the corner where the piano sat. Facing you, above the piano, was a clock. The front of the school and half of the east side were covered with blackboards. In front, in the middle, was the teacher's desk with a brass hand-bell sitting on one corner. Centered at the top of the front wall was a picture of George and Elizabeth. At the top right hand corner of the front blackboard, a clever display of maps, hung like roller blinds, was our window on the world. Each was unashamedly adorned with a picture of a chocolate bar, in homage to the benefactor.

Proceeding around the room clockwise, you passed the eastern wall blackboard and came to a narrow window facing east. Finally, on the left side of the door there was a tall cupboard that held school supplies and books.

Did we supply our own scribblers? They all seemed to have the Times Tables on the back, which suggests a single source. Pencils were probably our own responsibility since they were so prone to lead breakage by the overenthusiastic, or to being reduced to nubbins at the hands of children mesmerized by the grinding of the pencil sharpener. Wax crayons, as well, were likely our own since they could be exhausted quickly by those who PRESSED TOO HARD.

The old school was also the community centre. It later became that, in fact, but by that time, increased mobility had tended to diffuse community activities, and people began to travel to Meadow Lake and Goodsoil and other centres for recreation. When the old school was still functioning as a school, it was the central point that could be reached easily by the, at that time, overwhelmingly horse-drawn community. It was where we gathered for dances (I remember Mr. Shaw circling the room at interludes, slicing slivers of wax onto the floor to improve the performance), fowl suppers and whist drives. It was often used during the summer by whichever Christian denomination had decided to benefit us that year. Community events at the school often involved the unlimbering of a coal oil stove that ordinarily lay cloistered in a bench cupboard at the back of the room. When assembled, it had two burners sustained by an upside-down glass jug of kerosene that compensated for the draw on its contents by allowing irregular gurgles of air into the jug.

On rare occasions, distant public officials would appear to give uplifting talks, that were suffered in anticipation of the main attraction, a moving picture. Granted that these were usually about topics such as ploughing straight furrows, or cleaning grain, it was still a glamorous art form. They often ran a cartoon before the serious stuff, but it was all wonderful. I can't remember whether or not they had sound. The portable generator would have drowned out any that might have been, in any case.

Another community event of great drama was occasioned by the visits of the public health doctor and nurse. Immunization was clearly a good thing, even in our remote, innocent circumstances. You had to wonder, though, whether the efforts were

sufficiently comprehensive. It seemed that despite their ministrations, we all came down with measles, mumps, whooping cough, chicken pox and other maladies at annual intervals. A Rollo Park astrologer could target the year of your birth as easily by

identifying the prevailing illness that accompanied it, as with reference to celestial phenomena.

The important thing about the immunization sessions was that they allowed the big kids to terrify the little kids with tales of blunt needles, bent needles, needles poked through arms, needles broken off in arms, and with accounts of post needle traumas of

hideous character and dimension. My peripatetic life has occasioned many subsequent immunization sessions, and even with the passage of years and the wisdom of experience, I half expect the doctor's office to be full of howling children when I enter.

The old barrel heater and the tin fire screen around it that became festooned with woolen mitts in winter; the sudden odor of smoldering mitts and socks emanating from it; the long chimney pipe that traversed the room. In comparison, the central heating system of the new building lacked character and utility.

The windows of the new school were deliberately set at a height that let in light, but prevented an easy view of the road. This meant that when a truck or tractor or snowplow went by, everyone had to stand up to catch a glimpse, and the teacher had to shout at everyone to sit down. In the old school, the windows were set for easy scanning of the horizon. You did not have to disrupt proceedings to see whose truck was passing, or that Corky Flannigan was burning fire breaks around his granaries. Today we would call the old building "user friendly".

The desks in the old school were fine instruments for serious pedagogy. Cast-iron frames defined the contours of the gang desks where everyone sat two-by-two, except for a row of small, single beginners' desks on the window side, and a larger row of single, older students' desks on the other. Opening the lid of a two-by-two desk required the agreement of both parties involved, a fact that today would likely be seen as freighting academy with sinister political content. The old desks had a quality of purpose about them that was lacking in the single unit drawer/seat/arm rest/writing top versions that replaced them. In retrospect, the old desks were much more politically correct in that they inconvenienced left- and right-handers equally, whereas their replacements were for right handers, period.

When you entered the old school and turned left, there was a box cupboard on your immediate left with a water pail on top and firewood underneath. A step further and the heater was on your right, while on your left a bench under the window was generally loaded with lunch pails and filled beneath with boots and rubbers. Pegs on the wall in front held outerwear.

Turning right, you went past the three large windows to the corner where the piano sat. Facing you, above the piano, was a clock. The front of the school and half of the east side were covered with blackboards. In front, in the middle, was the teacher's desk with a brass hand-bell sitting on one corner. Centered at the top of the front wall was a picture of George and Elizabeth. At the top right hand corner of the front blackboard, a clever display of maps, hung like roller blinds, was our window on the world. Each was unashamedly adorned with a picture of a chocolate bar, in homage to the benefactor.

Proceeding around the room clockwise, you passed the eastern wall blackboard and came to a narrow window facing east. Finally, on the left side of the door there was a tall cupboard that held school supplies and books.

Did we supply our own scribblers? They all seemed to have the Times Tables on the back, which suggests a single source. Pencils were probably our own responsibility since they were so prone to lead breakage by the overenthusiastic, or to being reduced to nubbins at the hands of children mesmerized by the grinding of the pencil sharpener. Wax crayons, as well, were likely our own since they could be exhausted quickly by those who PRESSED TOO HARD.

The old school was also the community centre. It later became that, in fact, but by that time, increased mobility had tended to diffuse community activities, and people began to travel to Meadow Lake and Goodsoil and other centres for recreation. When the old school was still functioning as a school, it was the central point that could be reached easily by the, at that time, overwhelmingly horse-drawn community. It was where we gathered for dances (I remember Mr. Shaw circling the room at interludes, slicing slivers of wax onto the floor to improve the performance), fowl suppers and whist drives. It was often used during the summer by whichever Christian denomination had decided to benefit us that year. Community events at the school often involved the unlimbering of a coal oil stove that ordinarily lay cloistered in a bench cupboard at the back of the room. When assembled, it had two burners sustained by an upside-down glass jug of kerosene that compensated for the draw on its contents by allowing irregular gurgles of air into the jug.

On rare occasions, distant public officials would appear to give uplifting talks, that were suffered in anticipation of the main attraction, a moving picture. Granted that these were usually about topics such as ploughing straight furrows, or cleaning grain, it was still a glamorous art form. They often ran a cartoon before the serious stuff, but it was all wonderful. I can't remember whether or not they had sound. The portable generator would have drowned out any that might have been, in any case.

Another community event of great drama was occasioned by the visits of the public health doctor and nurse. Immunization was clearly a good thing, even in our remote, innocent circumstances. You had to wonder, though, whether the efforts were

sufficiently comprehensive. It seemed that despite their ministrations, we all came down with measles, mumps, whooping cough, chicken pox and other maladies at annual intervals. A Rollo Park astrologer could target the year of your birth as easily by

identifying the prevailing illness that accompanied it, as with reference to celestial phenomena.

The important thing about the immunization sessions was that they allowed the big kids to terrify the little kids with tales of blunt needles, bent needles, needles poked through arms, needles broken off in arms, and with accounts of post needle traumas of

hideous character and dimension. My peripatetic life has occasioned many subsequent immunization sessions, and even with the passage of years and the wisdom of experience, I half expect the doctor's office to be full of howling children when I enter.