|

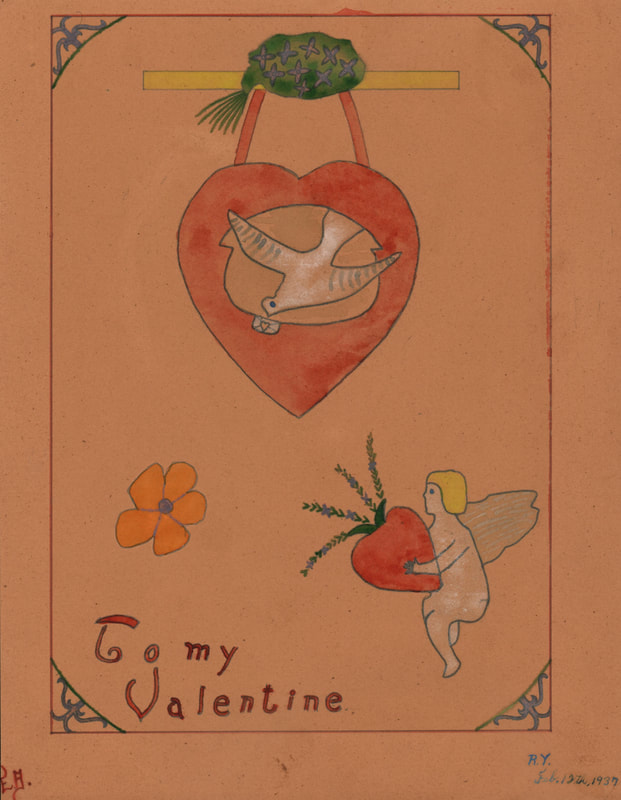

The Middleville and District Museum has several Valentine cards in its Collection. The common themes of cupid figures, flowers, hearts and doves are depicted in many of them. In some cases, the cards were made into post cards and were sent through the mail with a handwritten personal message. In school, students would be tasked with drawing valentine themed artwork. Be sure to check out the Museum's extensive greeting card collections for various holidays on your next visit.

0 Comments

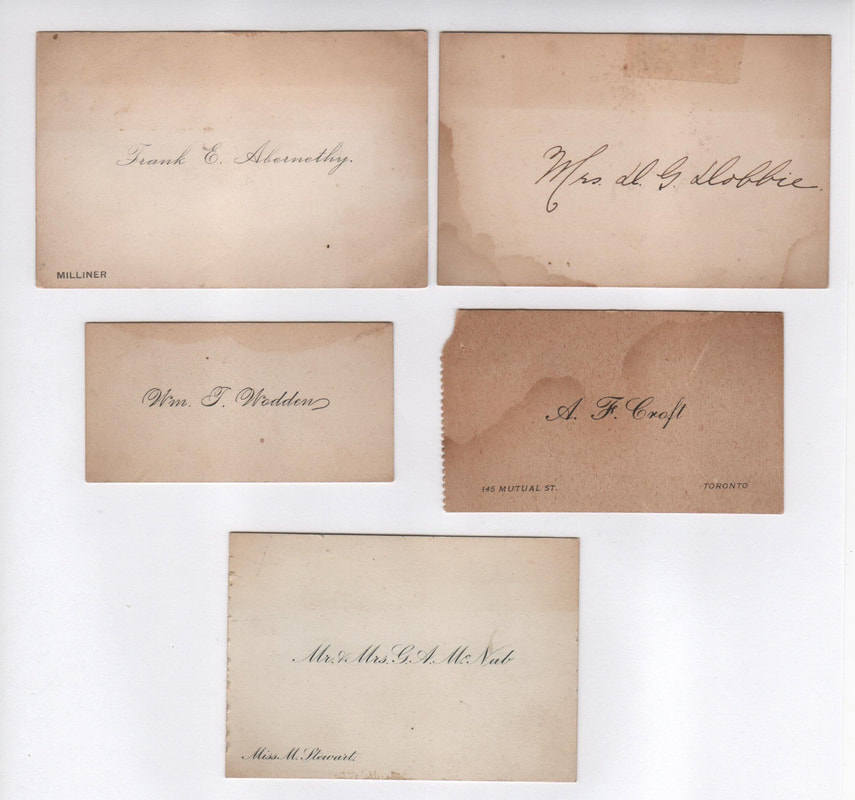

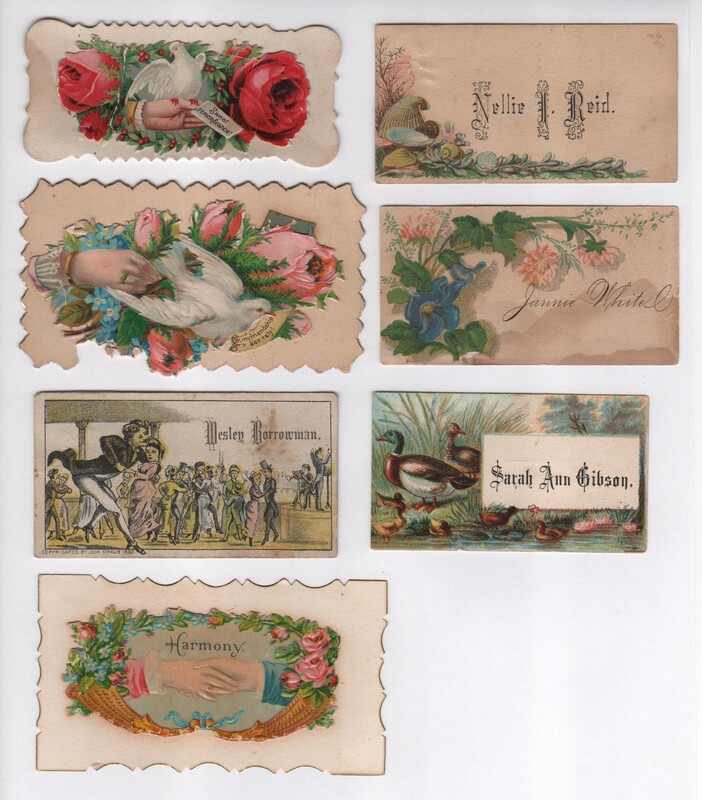

Calling Cards or Visiting Cards were found in France as early as the 18th century and their use spread through upper class society all across Europe. They were considered an essential part of the daily lives of those with wealth and influence. The custom began with simple cards bearing a printed name used to announce one’s arrival. Victorian society took the cards to a whole new level of intricacy of design. The evolution in the embellishments of the cards reflected the development of printing practices and innovation in technologies as well as aesthetic preferences of the day. Colour, artistic design and fancy script became fashionable. Calling cards often had adornments of doves, young women, kittens, hearts and hands. The edges were embellished with such things as ribbon, cloth fringe, scalloped borders and flaps to conceal a secret message. Calling Cards had a few additional common purposes. The cards were used to express congratulations, acknowledgment of kindness, condolences and arrival or departure. Calling Cards were presented at the door and collected on a small, ornate silver tray designated for that specific purpose. A full tray of cards suggested a level of popularity and social stature. Cards from prominent people would be carefully placed on top so they would be visible and impress other visitors. If the host or hostess was at home and wished to receive the visitor, the guest would be admitted. An absent host or hostess would find a card that had been left upon their return home. Etiquette dictated a card be sent to the person who left their card. If a reciprocal card was not sent, that reflected a social snub. The woman of the household was usually tasked with receiving and distributing calling cards. The gender and marital status of a person determined the dimensions of their calling card. A gentleman’s card would be designed to fit in a breast pocket. A lady’s card was larger. Calling Card cases might be made of silver, tortoiseshell, ivory or mother of pearl. A folded corner on a card also signified a certain message. A top left corner folded down conveyed congratulations, while a lower left corner fold was a message of condolence and a lower right corner fold indicated a long absence coming up.

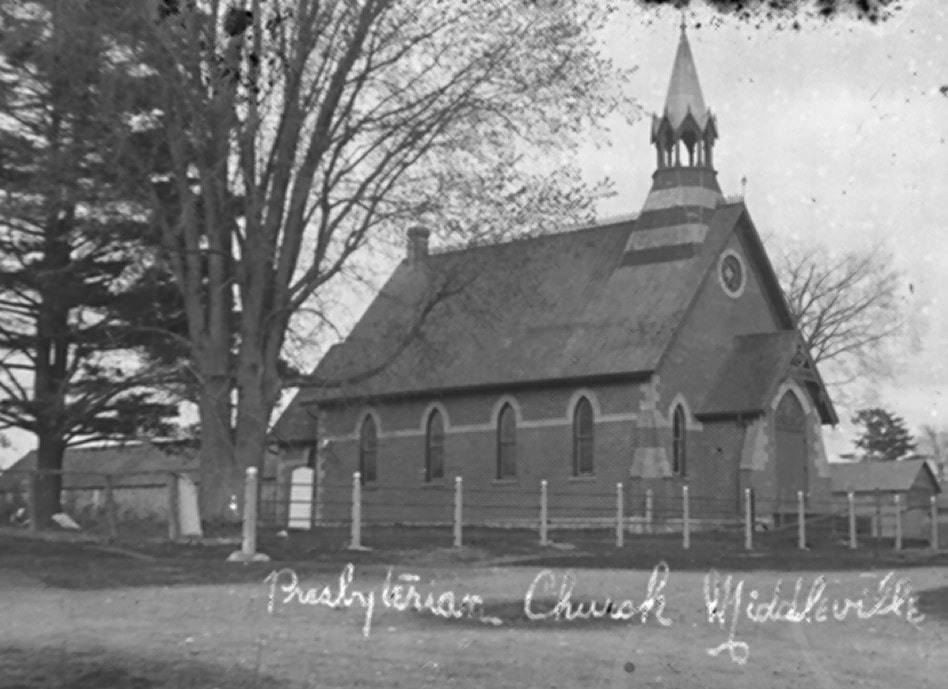

Calling cards were a means of establishing and strengthening relationships between people. With the emergence of penny post cards and eventually the telephone, social interactions changed over time and the calling card custom became less prominent. The modern practice of giving potential acquaintances a business card with contact information on it is a relic of the original Calling Card. Middleville and District Museum has a display of beautiful Calling Cards with examples of the plain, cream coloured cards with a simple name printed on each, as well as the colourful, ornately embellished cards. You may recognize a few familiar names. Be sure to view these Calling Cards in the parlour exhibit on your next visit to the Museum. The original plans for the purchase of the West half of Lot 15 on Concession 6 in what is now known as Middleville included a Presbyterian schoolhouse, a Church and a burial ground for members of the Church. In an early photograph, St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church has a few white tombstones visible at the north side of the Church. Horse sheds can also be seen extending from the rear of the Church. The edge of the horse sheds are believed to form the south perimeter of the graveyard behind the Church. Sadly, the original plan and records for this graveyard were lost when the Clerk of Session’s home where they were kept burned down.

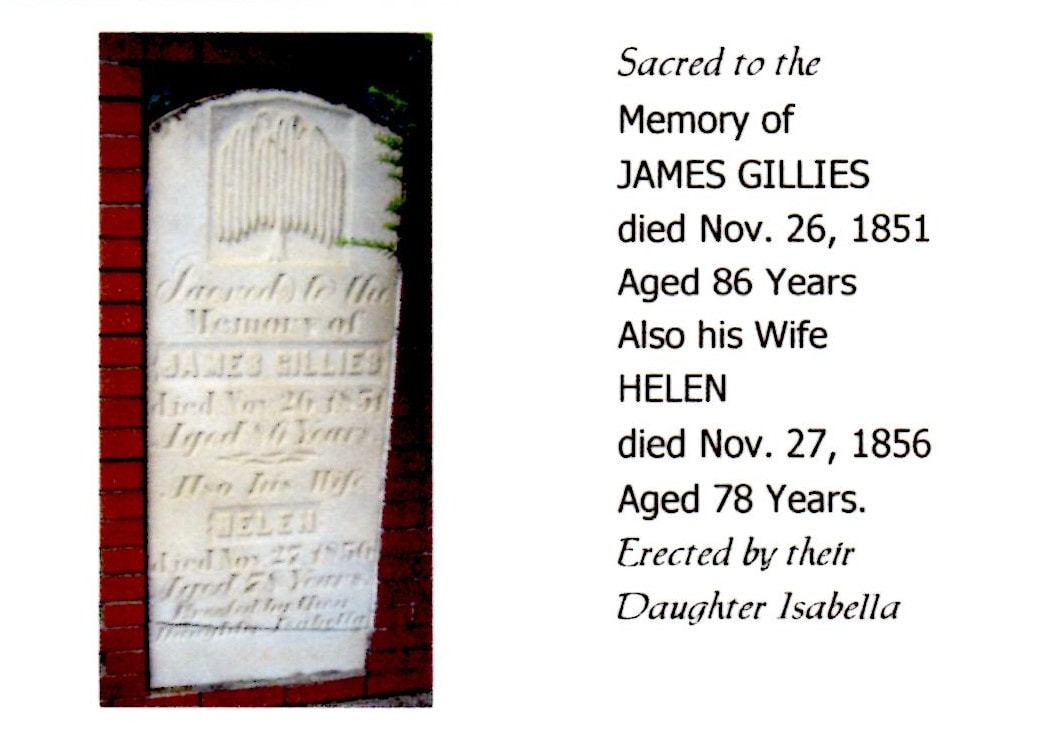

In the 1800’s, little was known or understood about disease and so a concern arose within the village of the possibility of seepage from the graves of people who had succumbed to diphtheria and other deadly diseases of the time into the nearby community well water. An initiative was made to purchase land outside the village boundaries for a burial ground where remains could be moved. In 1873, two acres of land were purchased and Greenwood Cemetery was opened on Lot 17, Concession 6. The Cemetery records state that some of the graves from the Church yard were moved to the first few rows of the new graveyard. Over the decades, the graveyard at the Church fell into an unkept state. It was reportedly scythed once a year, but the grass and weeds soon overtook the old tombstones. Little money or time could be afforded for the upkeep of the site. Some attempts were made to restore the site in the 1930’s, but the task proved too difficult and some of the crumbling stones that could be salvaged were moved to the shed to be stored. In the late 1960’s, another attempt at restoration was made and in the 1970’s a bequest made in the will of David A. Gillies, a descendent of James Gillies, provided the money for a properly funded restoration project to be undertaken. The Gillies family were the first occupants of the nearby Herron Mills site before selling it to the Herron brothers. James Gillies is believed to be the first burial on the pioneer graveyard at the Presbyterian Church in 1851. His wife, Helen Stark Gillies was buried beside him in 1853. It was the restoration of his ancestor’s final resting place that prompted David Gillies to ensure money was dedicated for this work. The actual graves of James and Helen Gillies were originally marked by a small elm tree planted beside their final resting place. The elm tree grew to full size over the decades, but is long gone. Local volunteers worked to erect a memorial wall patterned after the one built at Upper Canada Village where gravestones were salvaged and relocated into a series of red brick walls. In Middleville, twenty-five gravestones were set into the seventy metre long wall built on top of the original graveyard. Work on the wall was completed in 1971 and on Sunday, August 6th, 1972, a dedication service was held at the Middleville site. Jesse Stewart Gillies, widow of David Gillies, was on hand for the ceremony. Special guest speaker, Dr. Charlotte Whitton, former mayor of Ottawa, gave remarks. This was fitting as Dr. Whitton had written a book about the Gillies’ family legacy in the local lumber business. In the years since the wall was built, a flowerbed running along the front of the gravestones has been maintained. Volunteers tend the flowers each year and many people who pass by are inspired to photograph this intriguing monument to the past. The Middleville and District Museum volunteers are hoping to research and find more information about the people whose names are on the gravestones embedded in this wall and those whose grave markers were lost. The parameters of the original gravesite are not well known and with the loss of the markers were lost. The parameters of the original gravesite are not well known and with the loss of the original official records, gathering information about the actual site proves challenging. The volunteers of the Museum are hoping to hear from descendants of the people buried in the Pioneer Cemetery who may have researched their family history and be able to provide further clues to the story of the Pioneer Burial Ground in Middleville. If you have any information about this burial ground, please reach out to the Museum at middlevillemuseum@gmail.com. The gravestones have been photographed and can be found online with inscriptions. The first settlers in the Middleville area built a log schoolhouse. soon after arriving. The first known Presbyterian Church service was recorded at Young’s Schoolhouse in 1821. A meeting was held to plan for a land acquisition of an acre from the northwest corner of the west half of Lot 15 on Concession 6. Money came from Scotland in 1823 and this land was soon purchased from the landowners, James and Jean McIntyre, for a sum of three pounds and fifteen shillings. An additional fifteen shillings was paid as dowry for Jean. Trustees John McPherson and John Arnott signed the deed witnessed by William Scott and William Borrowman. The original plans called for a Presbyterian Schoolhouse, a Church and a burial ground for members of the Church. The first Church built was described as a white, frame rough cast. Rough cast refers to a slurry of lime, sand and gravel that would be plastered onto the wooden structure. Reverend Doctor Gemmill was the first minister and continued until 1828 when he withdrew. The Church was without a minister until 1831 when Rev. Wm McAllister was sent from Scotland. In 1890, the rough cast Church was torn down and replaced by a brick structure that opened in February of 1892 and remains in use today. A corner stone was drawn by stone boat by Robert Pretty from the farm of Wm Langstaff. The stone was quarried from the nearby farm of Matt Somerville. The interior was decorated by James Luteman and the pulpit was donated by Margaret Pretty. The new Church was designated as St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church. Reverend W.C. Clark became the first resident minister when the Middleville Church separated from Lanark. A manse was purchased in 1863. In 1924, the Presbyterian and Congregational Churches of Middleville joined together to become part of the United Church of Canada. Over the years, the Middleville Church had many arrangements with other congregations. The most enduring relationship was with its sister congregation from the Hopetown Church. The proximity of the two Churches made working together a natural fit. The Churches became known as Trinity and the congregations had a strong bond. With the sale of Hopetown Church, the Middleville Church is the remaining worship site for both congregations. Today, the old, red brick Church continues to stand proudly on the corner of Wolf Grove Road and Concession 6 in Middleville and still welcomes a faithful congregation. The Church with its modern facilities is still used by the community and was where the Middleville and District Museum Board held its Volunteer Appreciation Dinner in January of 2023. Many things have come and gone in the community, but the Church on the corner remains. *Information sourced from notes compiled by the late Jean Rankin from the records of James Penman, Secretary . The old one room schoolhouses that once dotted the rural landscape have met a variety of fates. Some were sold and repurposed as homes, some burned to the ground or were dismantled and are gone and others stand abandoned and are testaments to the passage of time. In most cases the only legacy that remains are the memories of the students now in their senior years that tell the tales of days gone by. The Middleville and District Museum started in an old two story, stone schoolhouse that lives on for the enjoyment of generations to come. The old desks attached to each other, the wood stove that provided warmth and hot lunches and the water cooler with one dipper for all to use spark memories for visitors. The heavy, brass bell and strap on the teacher’s desk bring back stories of daily life in a one room schoolhouse where all the grades were taught by a single teacher. The playground swings are gone, but sometimes the woodshed and old water pump still remain. Old trees planted in rows by teachers and students on arbour day can be found along the front of the lots by a keen eye. Our ‘Down Memory Lane’ page tells the stories of families, communities and school days. Bob Burchill’s stories of his days attending a one room schoolhouse as a young boy in Rollo Park, Saskatchewan are featured there. Enjoy the following excerpt of Bob’s memories and then visit our Down Memory Lane page to find more of his school memories. The desks in the old school were fine instruments for serious pedagogy. Cast-iron frames defined the contours of the gang desks where everyone sat two-by-two, except for a row of small, single beginners' desks on the window side, and a larger row of single, older students' desks on the other. Opening the lid of a two-by-two desk required the agreement of both parties involved, a fact that today would likely be seen as freighting academy with sinister political content. The old desks had a quality of purpose about them that was lacking in the single unit drawer/seat/arm rest/writing top versions that replaced them. In retrospect, the old desks were much more politically correct in that they inconvenienced left- and right-handers equally, whereas their replacements were for right handers, period.

When you entered the old school and turned left, there was a box cupboard on your immediate left with a water pail on top and firewood underneath. A step further and the heater was on your right, while on your left a bench under the window was generally loaded with lunch pails and filled beneath with boots and rubbers. Pegs on the wall in front held outerwear. Turning right, you went past the three large windows to the corner where the piano sat. Facing you, above the piano, was a clock. The front of the school and half of the east side were covered with blackboards. In front, in the middle, was the teacher's desk with a brass hand-bell sitting on one corner. Centered at the top of the front wall was a picture of George and Elizabeth. At the top right hand corner of the front blackboard, a clever display of maps, hung like roller blinds, was our window on the world. Each was unashamedly adorned with a picture of a chocolate bar, in homage to the benefactor. Proceeding around the room clockwise, you passed the eastern wall blackboard and came to a narrow window facing east. Finally, on the left side of the door there was a tall cupboard that held school supplies and books. Did we supply our own scribblers? They all seemed to have the Times Tables on the back, which suggests a single source. Pencils were probably our own responsibility since they were so prone to lead breakage by the overenthusiastic, or to being reduced to nubbins at the hands of children mesmerized by the grinding of the pencil sharpener. Wax crayons, as well, were likely our own since they could be exhausted quickly by those who PRESSED TOO HARD. Robert Burchill Evidence suggests that Donald Munro of Galbraith may have been an itinerant weaver which meant he travelled from cabin to cabin through the woods and stopped at each one. His barn frame loom was easily taken apart and packed onto a wagon. As an itinerant weaver made his way through the countryside, he set up his loom at each home for a few days and was given meals and lodging in return for completing the weaving for each family that he visited. There would usually be a bench in the kitchen area of the cabin where he could sleep. All the weaving that needed to be done would be ready for the visiting weaver's arrival. No time was to be wasted while the weaver was at each cabin. It might be many months before he would return. When the itinerant weaver set out on his journey through the forest to visit his customers, he would carefully remove the wooden pegs that held the large beams of his weaving loom together. Using wooden pegs instead of nails meant it was easy to take the loom apart and pack its pieces onto his wagon. Each part of the loom was carefully marked with a number or letter so it could be matched quickly with a corresponding mark. Then when the weaver arrived at the home of a customer, he could carry the parts of the loom into the cabin and reassemble it to working order. The four large beams and four smaller beams were all quite heavy so the families would offer help to carry these pieces into the cabin and lift them into place as the loom took shape. When he emigrated to Canada in the early 1800’s, Mr. Munro brought the small, intricate parts of his barn frame loom and his tools with him that were easily carried on board the ship crossing the ocean. Once he had a cabin built, he set about the task of selecting the cedar that would be sturdy enough to make the beams for the frame of his loom. He used his tools to hew the beams to the correct length and width. He carefully notched holes and pegs that would go together to secure the beams as a frame. Then the parts he had so carefully carried from Scotland were fit into place between the beams. He had brought his wooden shuttle and other small parts with him, as well. He travelled with a stool that he would sit on as he pumped the wooden pedals, called treadles, that made the loom parts move back and forth to work together to create the weave. The linen or wool that the family provided would be woven into blankets, rugs and pieces of cloth to be sewn into clothes by the family. When the weaving was completed for the family, the weaver would take his loom apart and, with the help of the family, he would load it onto his wagon and travel to the next family requiring his weaving services. Most families would have spinning wheels, yarn winders and small looms they used for their everyday weaving needs. They would save up the large weaving projects for the travelling weaver's visits. The Middleville and District Museum has artifacts that were used in the entire weaving process as well as several samples of work done by early weavers in the local area. Be sure to visit the weaving and textile exhibits in the Middleville and District Museum when it reopens next season.

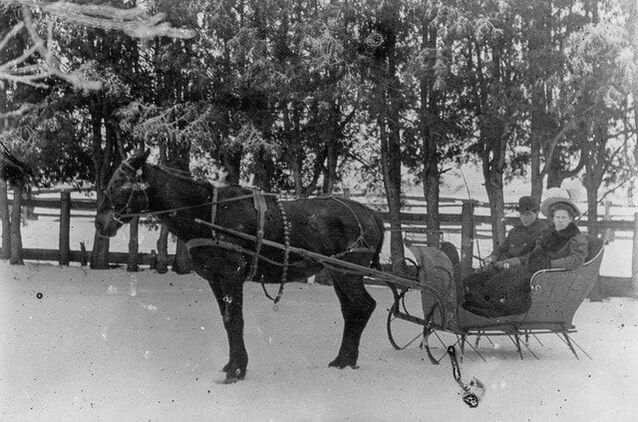

In the early 1800’s, the term cutter was first heard describing a light sleigh designed to carry one or two people that was used to travel over top of the snowdrifts in North America. This enabled people to get around in winter where roads did not exist and were not ploughed as a regular practice at that time. Keeping roads cleared was a later service. In 1857, James Pierport published a song entitled, 'One Horse Open Sleigh' that later became know simply as 'Jingle Bells'. This song mentioned the bells on ‘Bobtail’ ringing as the cutter travelled over the snow. This was actually required as a safety measure in many communities. Families listened for the distinctive bells on the horses of their relatives as they approached for a visit or return home. There were 'belly bells' that went around the girth of the horse and were "fastened to the harness backpad". "Shaft bells or chime bells had three or more bells fastened on a flat, steal strap (attached) to the underside of each cutter shaft". (C.Smith) By the 1820’s, James Goold of Albany Coach Works began to design a more decorative cutter known as the Albany Sleigh. Before this time, sleighs were often referred to as having a piano box style. The mail coach at the Museum is a good example of this construction. It was sturdy, but much heavier and required more horse power. The lighter cutter allowed use of a single, smaller horse. The cutter was mainly used as a quick way to get from one place to another for visiting, business and general errands. They were also regularly used to attend Church and community social events. By 1818, Portland Cutters designed by Peter Kimball of Maine were made with a ‘rolled dash’ at the front. High, long single piece runners allowed it to traverse the deep snow more easily. In 1889, the body design was rounded and known as a ‘swell body’. The Portland Cutter was more affordable than the Albany Sleigh which was often made more expensive by customized orders for paint colours and the seat upholstery fabrics chosen. The Portland Cutter had a straight back design which was easier to manufacture and cheaper to produce. Sears, Roebuck Catalogue was advertising the Portland Cutter for $20.30 in 1911. The Middleville and District Museum is thrilled to have received the donation from the Moulton family of what is believed to be an early 1900's Portland Cutter. It delighted visitors during the Victorian Christmas event at the Museum in November. Research points to the Moulton Cutter being a Portland Cutter. The distinguishing features of side doors and a special iron eagle head on the right end of the front dash board support this conclusion. The side doors were a fairly unusual feature and are believed to be a nod to the rising popularity of automobiles in the 1900’s. The doors were often deemed a novelty feature, but served a practical purpose by keeping the snow out of the cutter as it blew up around the sides. The eagle head was probably a reflection of the American production company. The Moulton Cutter will be on display when the Museum reopens on Victoria Day weekend. Make a note to see this gem.

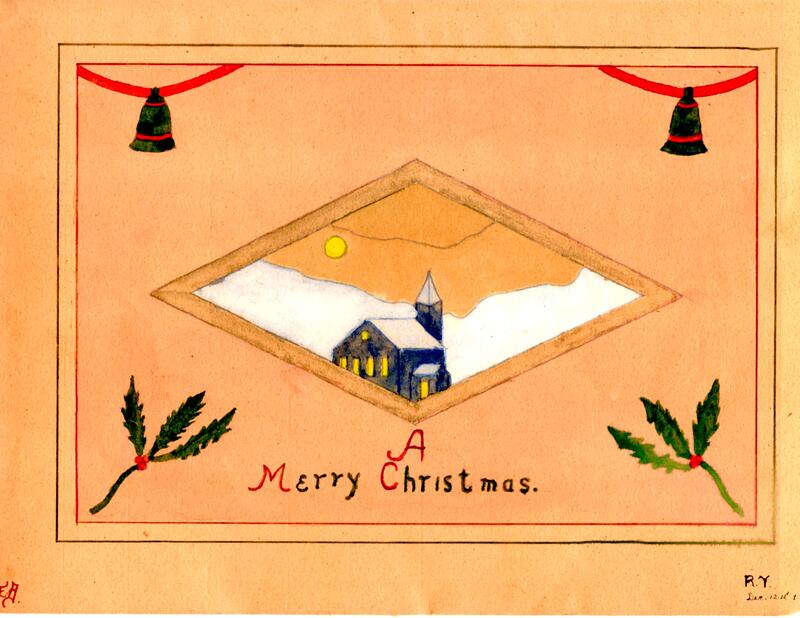

Christmas celebrated by local families in days gone by was full of traditions carried on for generations. A check of the pantry would determine the grocery list of supplies needed for pre-Christmas baking. Sweets would be made and tucked into simple packages ready for Christmas celebrations and to give to neighbours and friends throughout the season. Letters to Santa were written and Christmas cards would be posted. In the days leading up to Christmas, the family would plan a trek through the forest to pick out the best evergreen tree to be found. Once selected, the tree would be cut down with an axe and hauled back to the house. Furniture would be shifted aside and once the snow had melted off the branches the tree would be propped up in a stand. The family would be busy stringing cranberries and popcorn for garland. A few candles would be added to the tree in brass or tin holders that fastened to the sturdy branches with clips. The candles would only be lit for a brief few minutes 0n Christmas Eve due to the risk of the tree catching on fire. Glass bulbs would later replace the real wax and wick and be strung on an electrical card. In modern times, strings of lights are added to every surface inside and outside for the entire Christmas season. Garlands of evergreens were popular to decorate the fireplace mantles in early days. With the passage of time, artificial trees and garlands were produced and were adopted as a way to avoid the messy clean up of needles from the real evergreens. Many families have gone back to real garlands and trees. These are available at Christmas tree farms and local greenhouses. The annual stroll through the wilderness has been replaced by the yearly trip to select the ideal tree from the tree lot for those who don’t have their own natural supply. The trend toward using natural elements to decorate the tree and mantle has become popular once more. Families are opting for a live tree and garland and using forest items such as pinecones and branches to adorn their homes. Dried cranberries and oranges are sometimes used to harken back to the original decorations used by generations before. The Middleville and District Museum volunteers found some vintage Christmas ornaments and fashioned some burgundy and light pink bows along with two long white sashes to decorate the old schoolhouse door in a Victorian style for the season. A few pine cones were tucked into some natural garland draping the handrails.

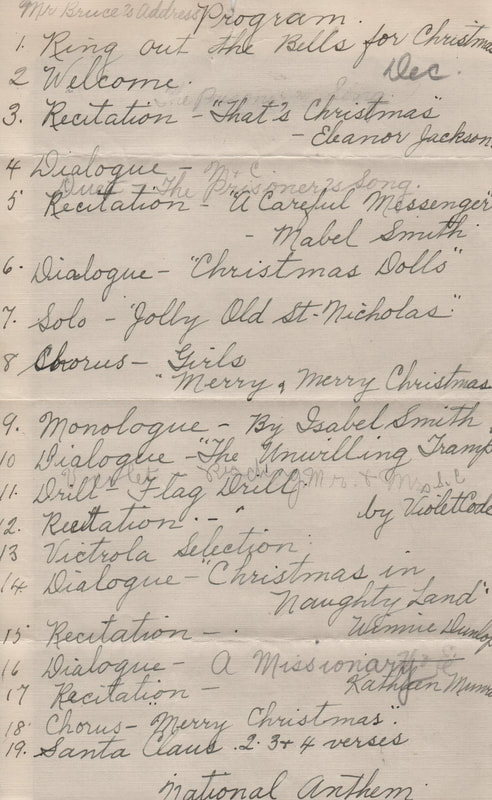

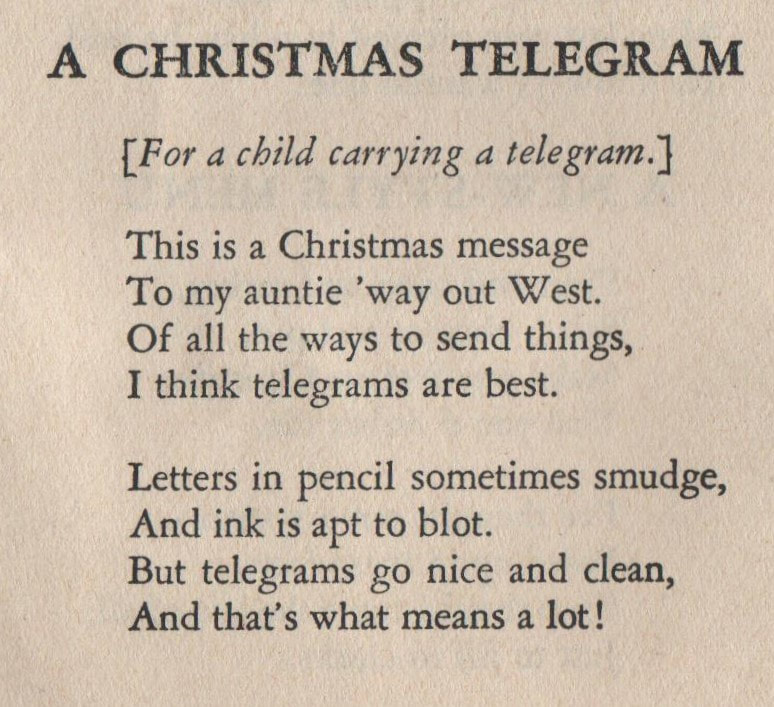

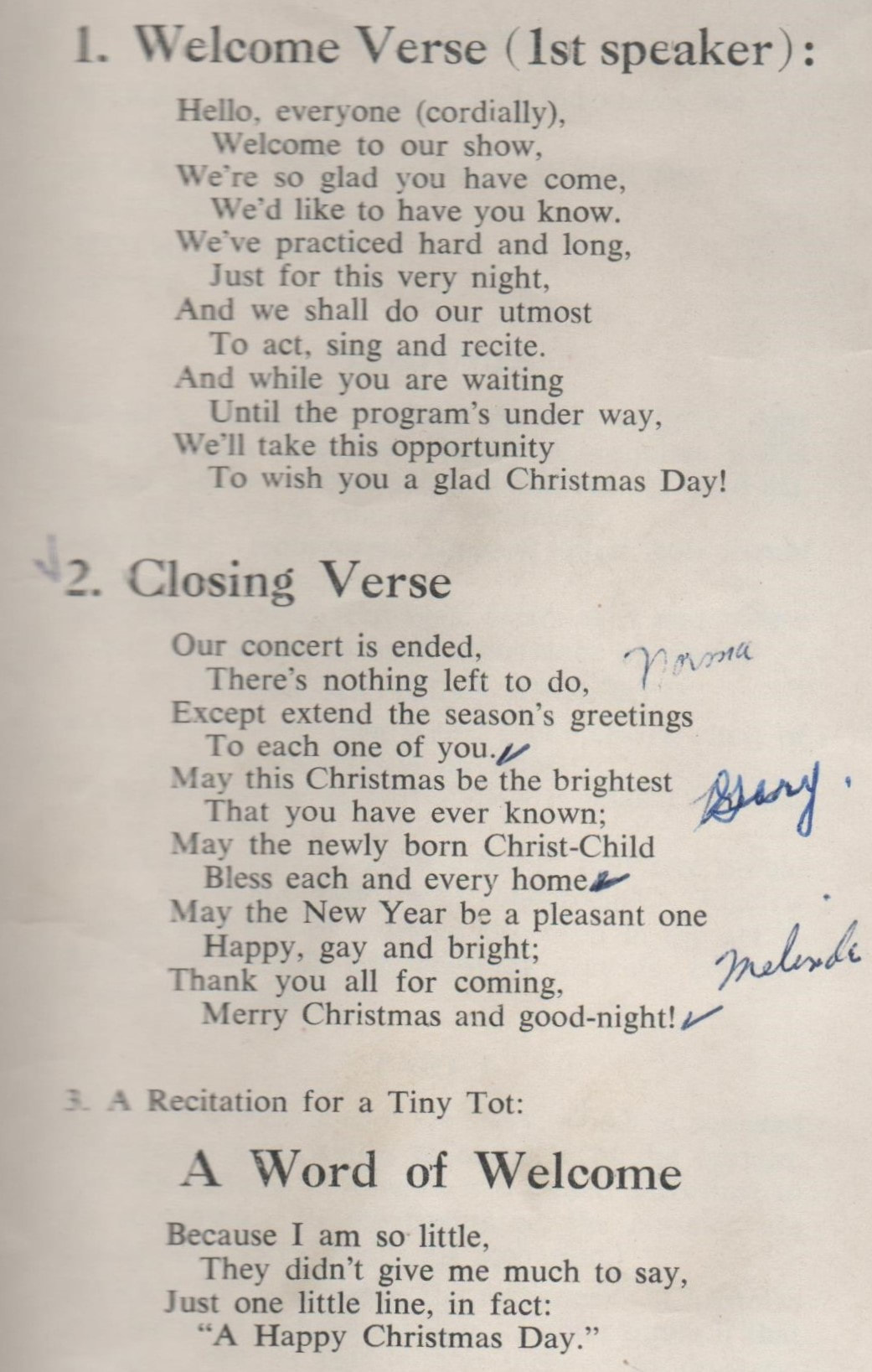

Mr. Robert Burchill of Ottawa, has shared some of his Christmas concert memories with the Museum. Bob and his wife are regular visitors and have donated items to the Museum over the years. Bob was inspired to share his memories when on a visit to the Museum this past season, he found out about the Museum's storytelling project. He offered to send along some memories he had written down. The following are some of Bob's childhood memories of Christmas concerts. Rollo Park School in Northern Saskatchewan was eight grades in one room. It was built of logs, and heated by a wood burning stove. It served as the community center as well as the school. One of the more popular events was the Christmas Concert put on by the students under the direction of the teacher. The concerts were generally known as "Trees". "Are you getting up a Tree?" and "When is your Tree?" were questions of entirely sober quality in our neighborhood. Christmas Trees were not only celebratory. For many parents their quality was an important index by which the teacher's competence was judged. "That was a real good Tree" was a judgement that tended to transcend the event. The choice of play, of music, and of setting were important, but strictly secondary to the need for balance in the apportionment of roles and responsibilities among the members of principal families. Teachers had to employ excellent diplomatic skills to avoid familial affront. The Christmas Tree season was presaged by one of the older girls removing the alphabet from the blackboard border and replacing it with seasonal motifs, such as stars and snowflakes. These were executed with the aid of stencils, sheets of paper on which the motifs were outlined in fine holes. They were held up against the blackboard and patted with a chalk filled blackboard brush. The result was the transfer of the motif onto the blackboard. The lines of the motif were then thickened and the design finally colored with tinted chalk. Carol practice and play rehearsals began. Step followed step until the great day. Desks were removed from the schoolroom, and the stage units along with boards on blocks were brought in from their normal residence behind the school. Bed sheets were hung from the permanently installed wires and, presto, a theatrical environment as capable of producing surprise, wonderment and pleasure as any on Broadway or Leicester Square was ours. All subsequent Trees at Rollo Park tended to be judged against the one in which my eldest brother Gordon played the lead. It brought the house down. It may also have been the Tree at which I fainted during the final carol singing. I was carried outside and revived in time to see a friend’s father getting dressed as Santa Claus. This did not provoke a traumatic reaction as was expected. I had probably had my suspicions for some time, but, was happy to keep them to myself as long as apparent conviction produced the desired results. The Museum is happy to share these memories at this time of year. Other school days memories of Bob's will appear on our Down Memory Lane page in the new year. We hope reading Bob's memories will spark memories of you own Christmas concerts. The Museum has a publication called 'Everybody's Christmas Programs' from the Dramatic Publishing Company., 1939. It contains 150 pages of recitations. songs, drills, exercises, pageants, plays, skits, monologues and complete programs. It is part of the teachers' books collection. A second teacher's reference book contains recitations, plays and drills.

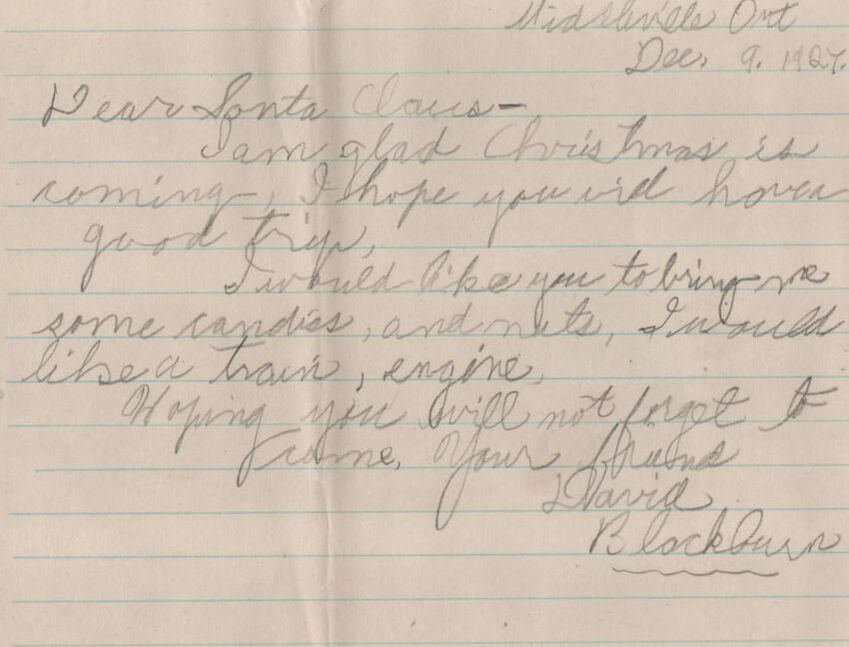

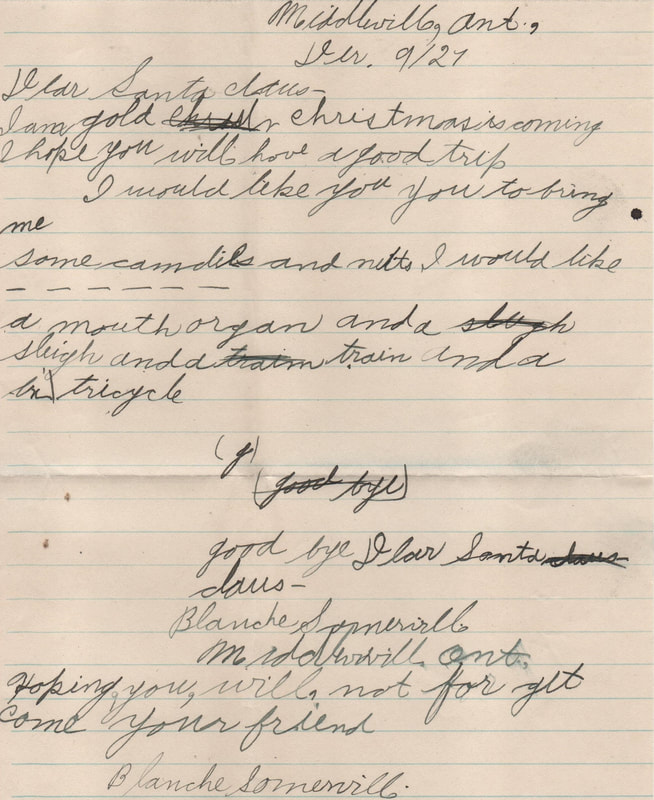

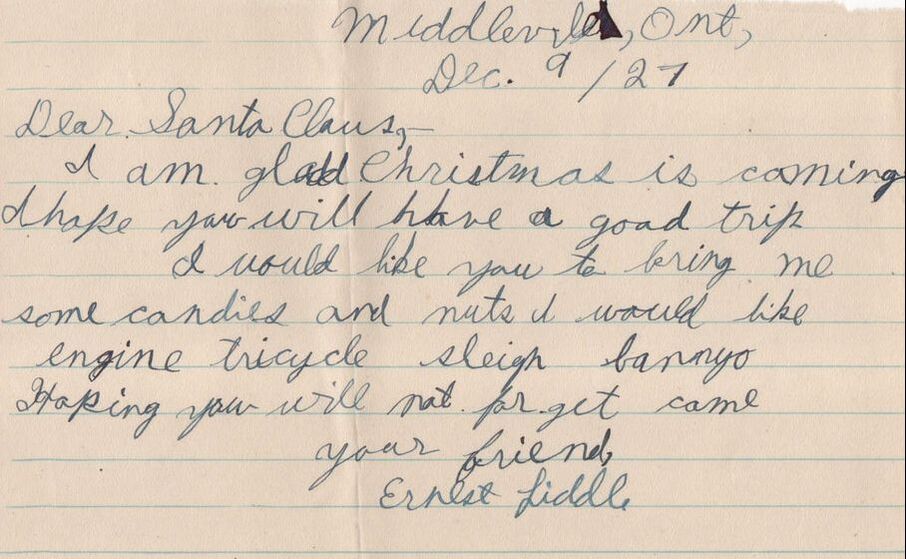

The exchange of letters between Santa and children seems to have begun with St. Nicholas leaving letters for children in their stockings. In 1823, the classic story, ‘A Visit From St. Nicholas’, was published. This story is recognized today as ‘T’was the Night Before Christmas’. The tale depicts a jolly character known as Santa Claus dressed in a red suit and travelling all over the world in a sleigh pulled by flying reindeer on Christmas Eve. This image of Santa Claus persists as the common modern day portrayal. In 1889, a cartoon shows Santa reading letters from children. Letters written to Santa commonly make references to the writer’s personal behaviour, wish lists of toys and good will toward Mrs. Claus and the reindeer. Some letters include a picture for Santa to enjoy and in more recent times a message about a snack of milk with cookies left on a table for Santa and carrots for his reindeer. In the 1970’s, a Canadian couple, Charlie and Verna Green from Minnedosa, Manitoba, had a box in their shop where children could deposit letters to Santa. Verna took on the task of replying to these letters. She sometimes responded to as many as 500 in a Christmas season. In 1982, Canada Post took on the task of answering letters using volunteers and established the famous H0H 0H0 postal code. Letters to Santa have evolved through the decades with the social and economic changes in society. The lists of wishes from children in these letters often reflected the times they were living in and the general wealth and well being of their families. in later years, catalogues would offer ideas for toys that could be ordered through the general store or eventually from home. The Museum has a small collection of letters to Santa from Eva Kemp's 1927 class. Several of the letters have been copied from a model provided by the teacher to practice penmanship and letter writing skills. The student would include individual requests in the last part.

|

AuthorThis journal is written, researched, and maintained by the volunteers of the Middleville Museum. |