|

Preserving all the wild berries and fruits that could be foraged from nature was a means of survival. A full larder well stocked for the harsh winter months ahead was essential. When the leaves of the maple trees began to turn to a varied array of yellow, orange and red, it signaled the time to harvest the autumn produce. Many jars of jams and jellies made from summer berries would already be on the cellar or cold storage shelves. Green pickles, ruby red chokecherry jelly and yellow squash would add to the rainbow of colours. The Middleville and District Museum has a few reference books on the library shelves that served as a guide for the proper preservation of the nature's harvest. From Grandma's Kitchen Middleville and District Museum Crabapple Jelly You will need: crabapples sugar (3/4 - 1 cup for each cup of juice) water (about 1 cup for 4 quarts of fruit) (5 cups = 1 quart) large pot or preserving kettle, jars, jelly bag or cheesecloth, vegetable masher, large bowl Wash fruit and remove the stems. Cook in a large pot with just enough water to keep the apples from burning. Heat to boiling and cook until the fruit is tender. Use a vegetable masher to crush the fruit. Dampen the jelly bag (or cheese cloth) and pour the apples and juice into the bag suspended over a large bowl. Let the juice drain into the bowl overnight. Measure the amount of juice collected in the bowl. Boil the juice for 10 minutes and skim off any foam collected on the surface. Add 3/4 - 1 cup of sugar for each cup of juice. Stir until the sugar is dissolved. Boil an additional 3 - 10 minutes until the syrup mixture jells. The syrup has reached the jelling point when it drops off a spoon and breaks apart. Use a candy thermometer to check for a temperature range of 216 degrees F to 220 degrees F. Pour the jelly into sterilized jars, leaving 1/2 inch at the top. Set aside to cool. Store in the refrigerator. Crabapples are among the fruit that have natural pectin and will jell without adding it. Preparing the jars: wash jars with soap and water. Scald in a water bath to sterilize by immersing (covering) jars in water in a deep pan and bringing the water to a boil. Boil for 2 minutes and let cool. Draining the juice: use a jelly bag or 1 square meter of cheesecloth folded into layers and suspend the bag or cloth over a bowl. Do not squeeze the bag during the draining process. Variation: Wash, stem and cut crabapples into quarters, removing the core. Cook in a pot with just enough water to keep from burning. Cook until apples are tender. Mash apples and serve warm. Baked Apples You will need: 6 medium cooking apples 1 cup orange juice or apple cider 1 cup rolled oats 1/2 cup brown sugar 1/3 cup slivered almonds, toasted 1 tablespoon flour 3/4 teaspoon cinnamon 1/4 teaspoon nutmeg 1/3 cup melted butter apple corer, baking dish with lid, pastry brush Slice 1/2 inch off the top of each apple and remove the core, stopping about 1/2 inch from the bottom of the apples. Brush with 1 tablespoon of orange juice or cider. In a bowl, combine oats, brown sugar, almonds, flour, cinnamon and nutmeg. Stir in melted butter until well mixed. Fill the apples with oat mixture. Place in baking dish. Pour remaining juice or cider over apples. Bake, covered, at 350 degrees F for about 50 minutes. Uncover and bake another 10 - 15 minutes. Variation: Core apples, as above. Combine 1/4 cup dried fruit, 3 tablespoons finely chopped nuts, 3 tablespoons honey and 1/2 teaspoon of spices (cinnamon, nutmeg) Spoon mixture into apples. Place apples in a slow cooker. Pour 1 cup apple cider over apples. Add a pinch of fresh ginger to slow cooker, if desired. Divide 1/4 tablespoon butter to top each apple. Cook on high for 2 1/2 - 3 hours. From: Better Homes and Gardens: 100 Best Apple Recipes 2020 Gooseberry Sauce This sauce can be used to top ice cream or biscuits. You will need: 5 cups gooseberries (washed and tailed) 3 1/2 cups white sugar 1 1/2 cups water Heat water and sugar in a pot, stirring until sugar is dissolved. Add gooseberries and cook, stirring until mixture is clear. Store in a jar in the refrigerator. Grandma's Easy Cucumber Pickles You will need: 32 cups ripe cucumbers (peeled and seeded) 5 cups white sugar 6 cups white vinegar 3 ounces pickling spices tied in a bag large pot Cut cucumbers into chunks. Dissolve sugar in vinegar and bring to a boil. Add cucumbers and spices in their bag. Boil until clear, about 30 minutes. To make your own pickling spice: Mix together a desired combination of these spices: 2 tbsp mustard seed, 2 bay leaves, 2 tsp dill seed, 2 cinnamon sticks (broken in pieces), 1 tsp ground ginger, 2 tbsp allspice, 2 tsp black peppercorns, 2 whole cloves, 1 tbsp celery seed, 1/2 tbsp chili flakes Store in an air tight jar. To make a pickling spice bag: use cheesecloth and cord Tomato Jam Relish You will need: 12 ripe tomatoes 2 1/2 cups white sugar 2 cups white vinegar 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1 teaspoon ground cloves 1 teaspoon salt Peel tomatoes. Hint: pour boiling water over tomatoes to loose skins. Place tomatoes in a pot with sugar and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer for about an hour, stirring as needed, to avoid burning. Add vinegar, cinnamon, cloves and salt. Boil until thickened to jam consistency. Store in jars in the refrigerator. Serve on meat or use as a relish. Chokecherry Jelly You will need: 3 cups chokecherries 3 cups white sugar 1/2 cup lemon juice water to cover cherries in pot 1 package fruit pectin 1 teaspoon butter (optional) pot with a lid (tall cooking kettle is best) masher, strainer, bowl jars with lids, canner for water bath Remove stems and wash chokecherries thoroughly. Put chokecherries in the pot and cover with water. Put a lid on the pot and bring to a boil. Then simmer until the fruit is softened (about half an hour). Remove from heat and gently mash the fruit. Put the fruit into a strainer over a bowl to catch the juice. Discard the pulp. Collect the juice and return it to the pot. Stir in the fruit pectin and lemon juice. Bring to a boil. Watch carefully to avoid boiling over. Hint: Add a teaspoon of butter to prevent the juice boiling over the top so easily. Add sugar and stir until dissolved. Boil juice mixture for about 15 minutes. Ladle the juice mixture into the jars leaving a half inch of space at the top. Put the lids on the jars and tighten slightly. Place the jars in a water bath just covering the tops by an inch. Simmer in the bath for about 5 minutes. Remove from water bath. Store jars in a cool, dark place. Check out all the recipes in Grandma's Kitchen on the Middleville and District Museum's website.

http://www.middlevillemuseum.org/grandmas-kitchen.html

0 Comments

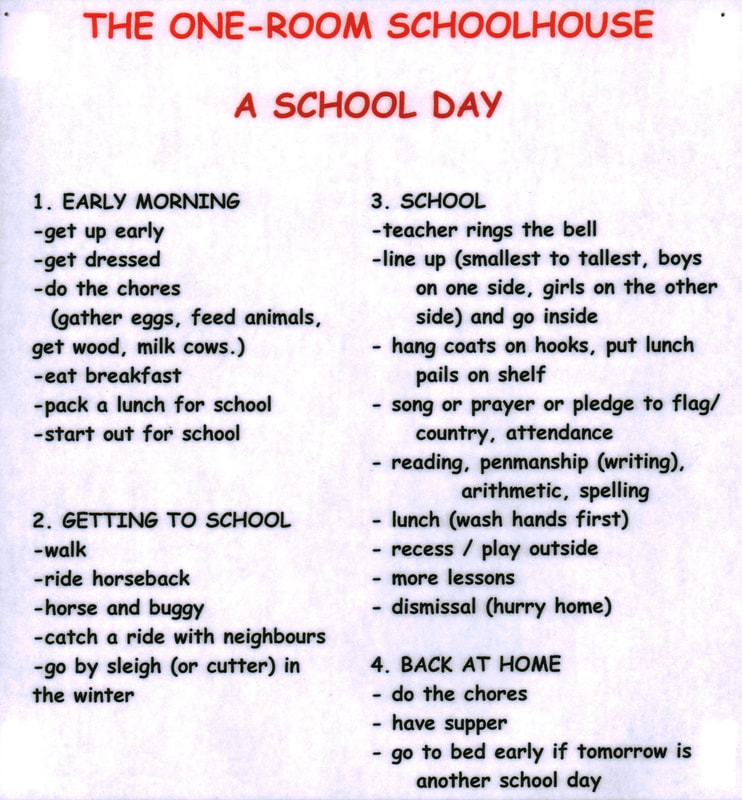

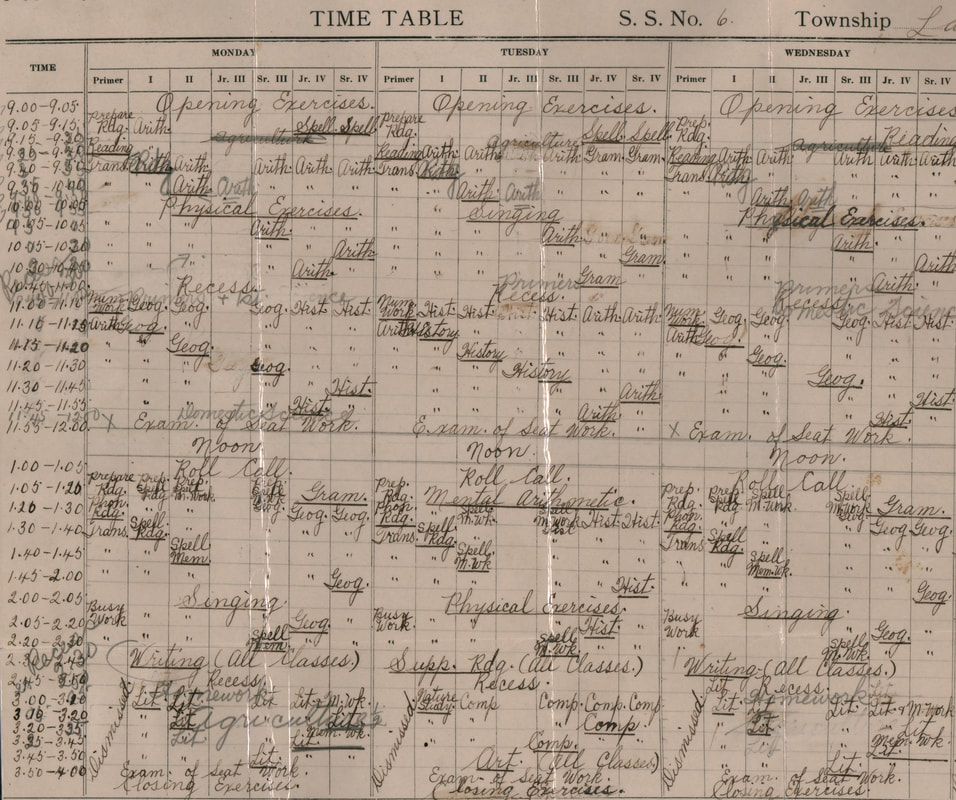

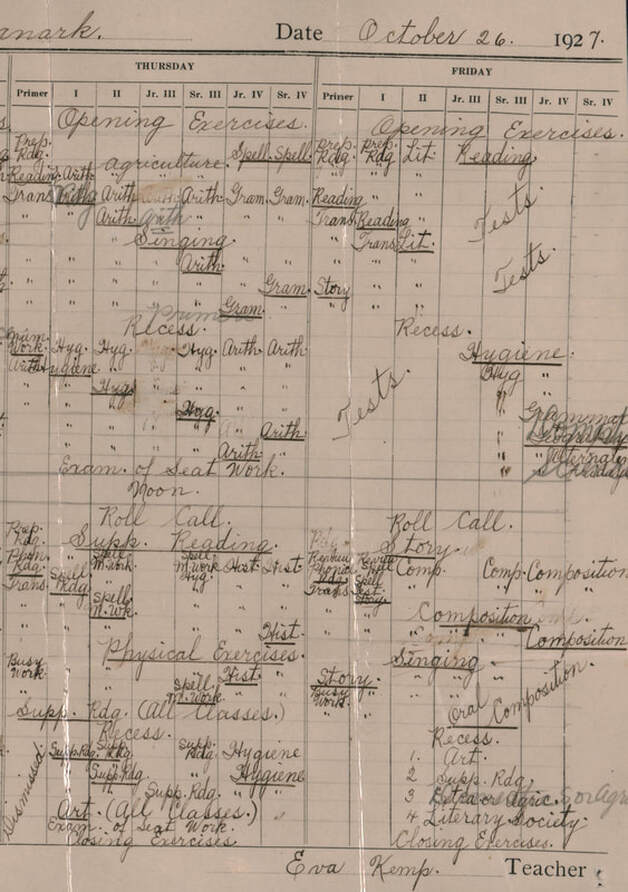

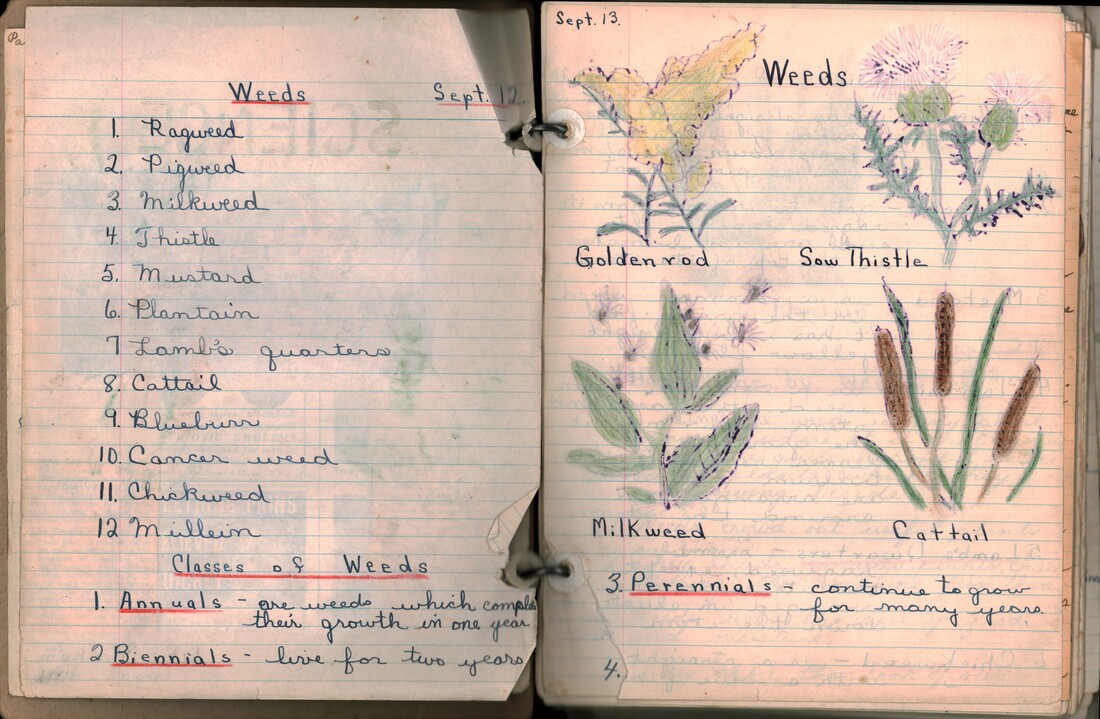

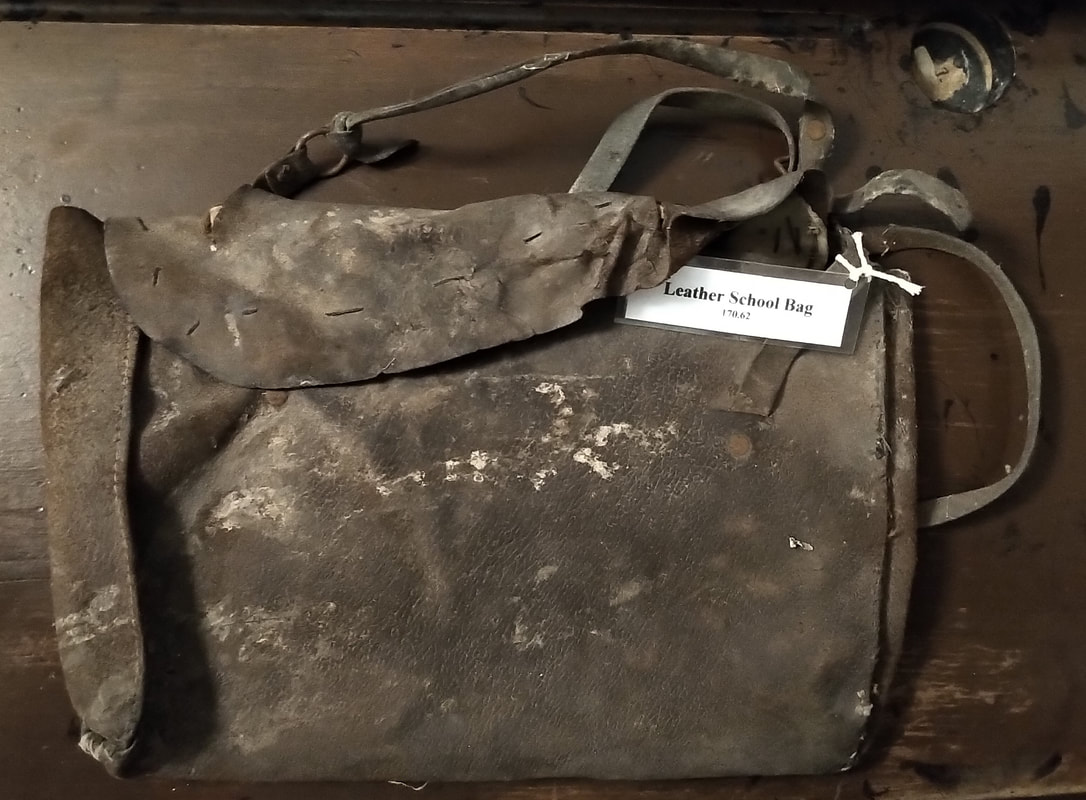

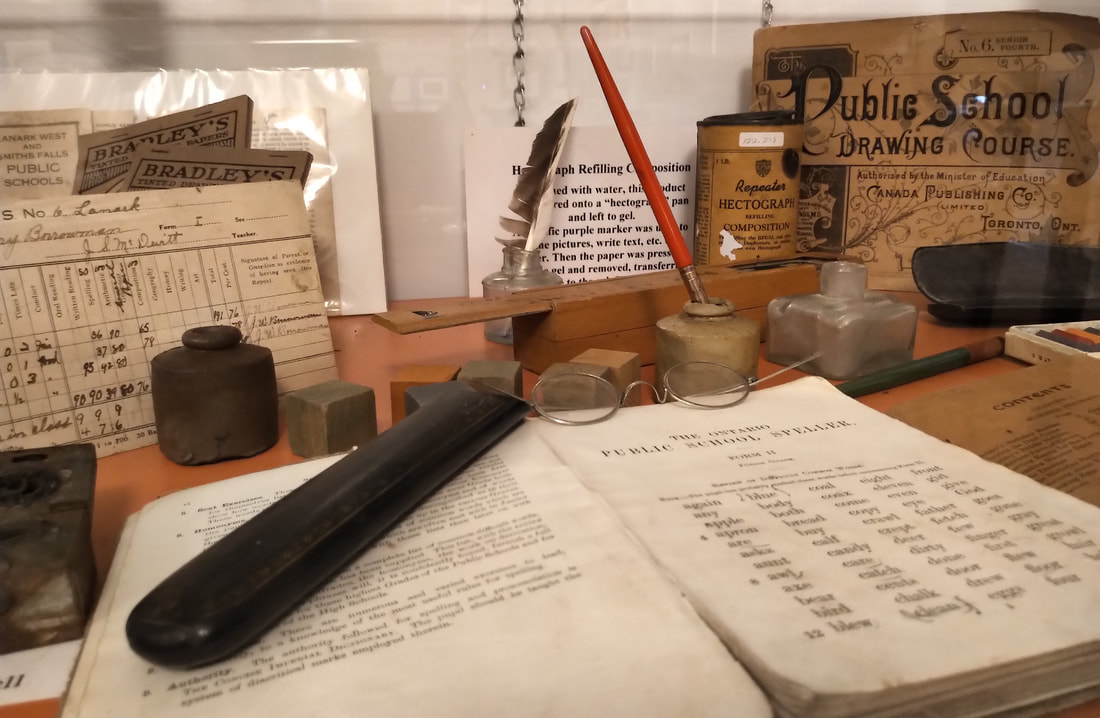

Times sure were different back in the days of the one room schoolhouse. Children and parents had a completely different daily schedule. Back to School in 1927 Eva Kemp's Classroom Timetable at S. S. # 6 Middleville School A time tested tradition: the 'First Day of School' photos The Middleville and District Museum has many artifacts and records of school in the years of the one room schoolhouse. The original part of the Museum is housed in the 1861 stone SS # 6 schoolhouse in Middleville. The other Lanark Township schools are represented by artifacts in the Collection and in records and photographs compiled by each school area: Boyd, Bulloch, Fergusons Falls, Galbraith, Herron Mills, Hopetown, James, Middleville, Pine Grove and Rosetta. There is also information on Poland School and Union Schools.

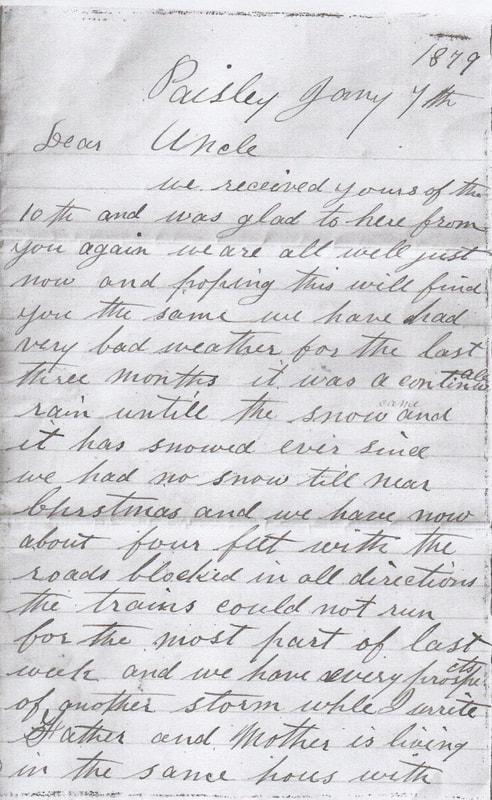

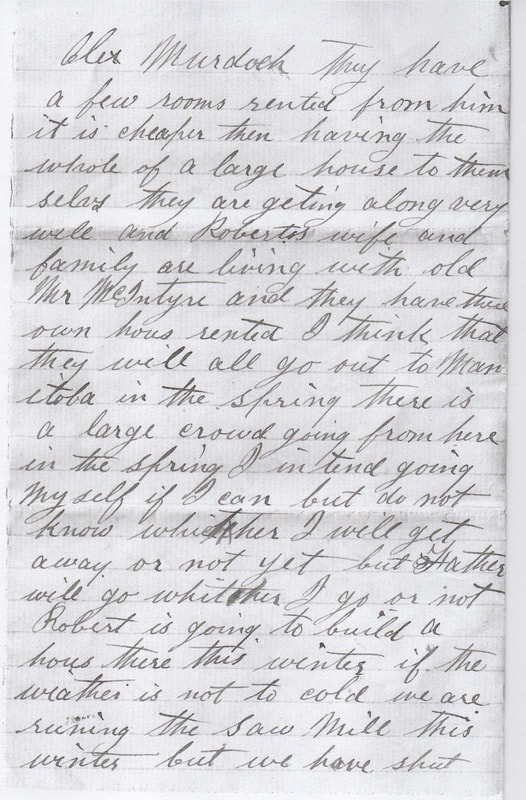

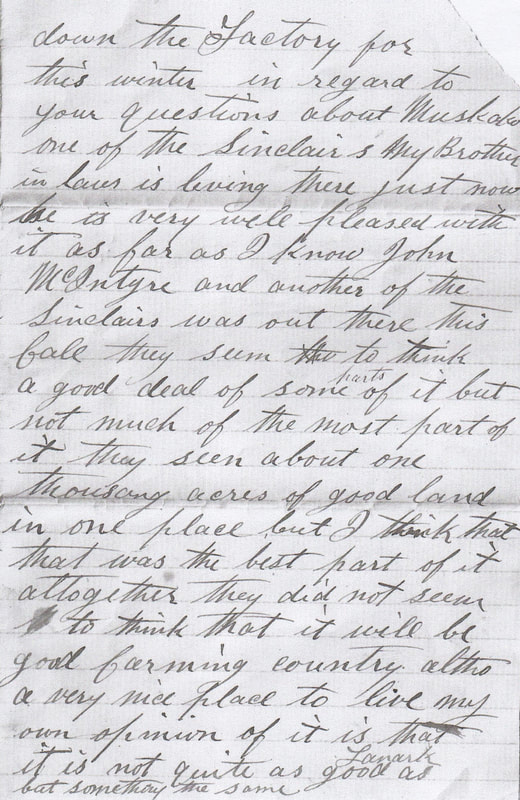

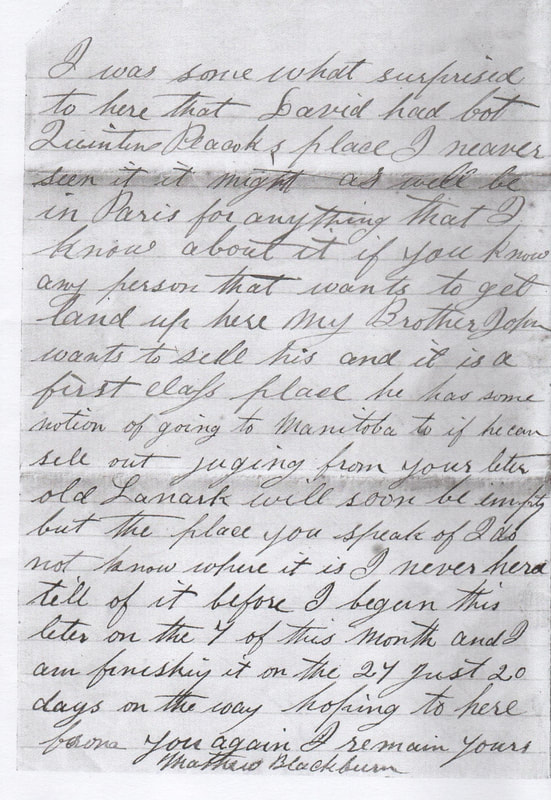

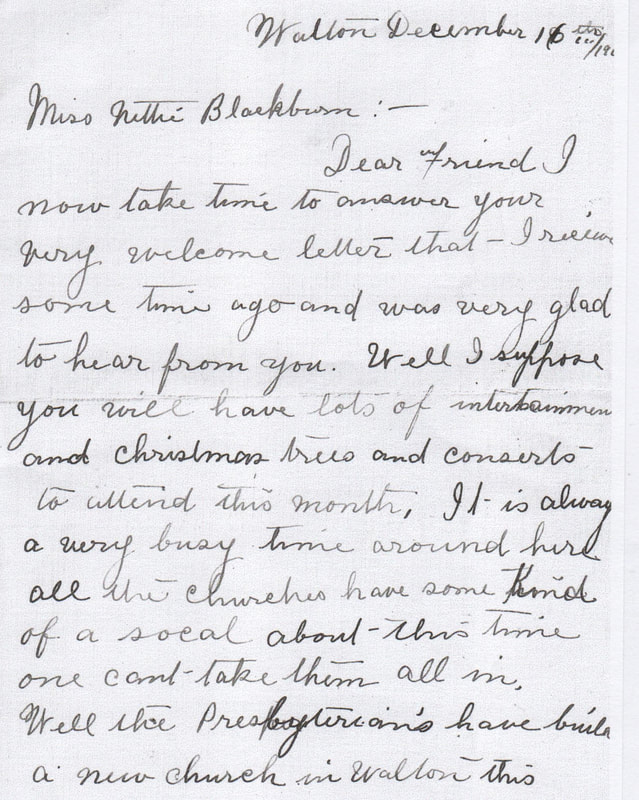

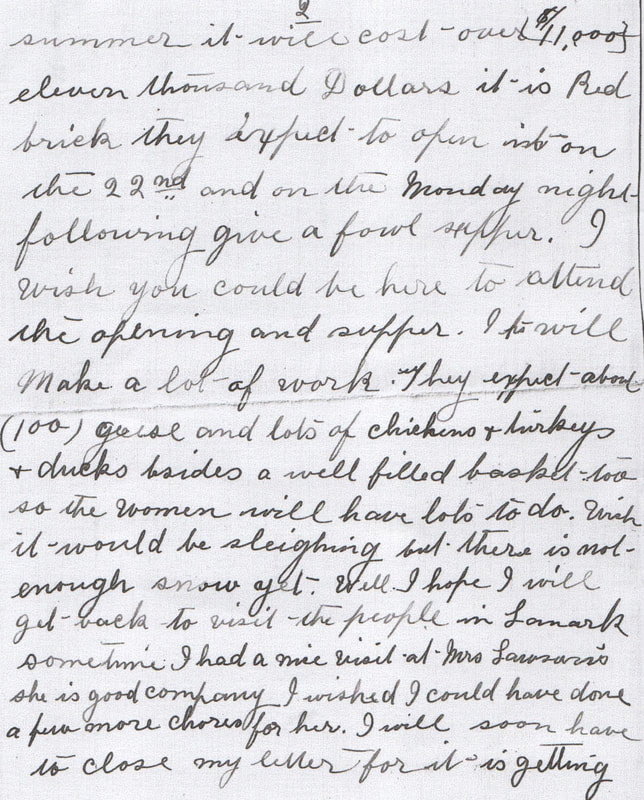

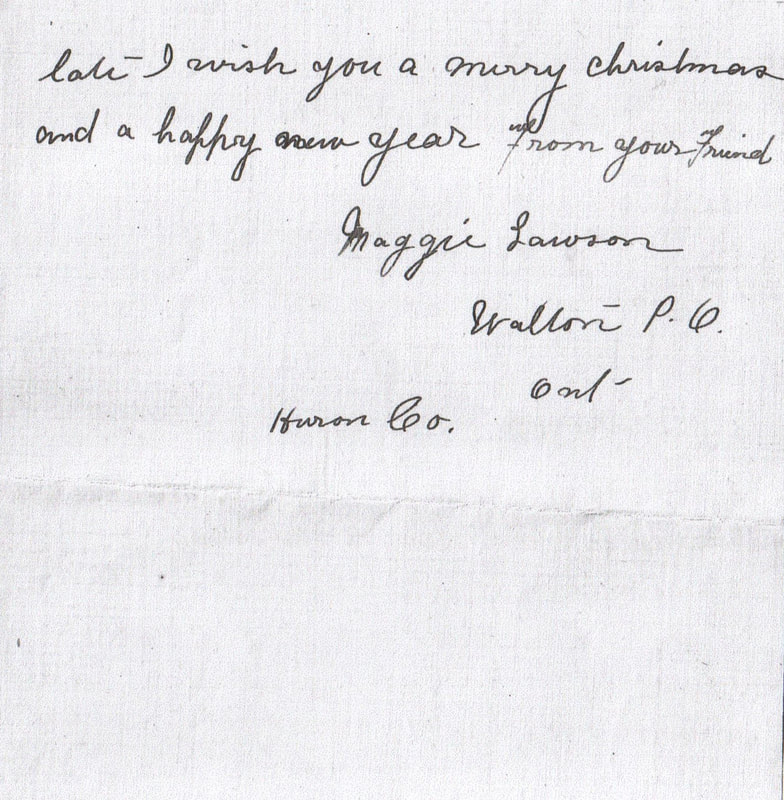

Be sure to take some time to look through the school histories and photos at the Museum on your next visit. Letters that have survived through time give a glimpse into the daily lives and thoughts of the people who scribed a message to friends and family members. Many letters recount a wish for more frequent correspondence that speaks to the desire for more human interaction in times of social isolation. Travel was more difficult in the past and news from loved ones far away was conveyed through letter writing. Details like dates, geographic locations, names and relationships were revealed in the text of letters. A written note often included weather and general circumstances of health and prosperity. A job might be described or a plan for travel to a different location forecast in the body of a letter. The clues hidden in plain sight in the lines of a letter can give important information leading researchers to pursue theories and uncover storylines of a family’s history. Significant events in the lives of people were recorded through letters. Reports of births, marriages and deaths were included in letters. Careers and vocations were often mentioned when writing to others. Community events would be described in correspondence. The Middleville and District Museum has several old letters that give insight into the lives of people at different times. Be sure to take a few minutes to read some of these old relics that have a story to tell on your next visit to the Museum. To find out what letters are available for reading, check out the Letters Index.

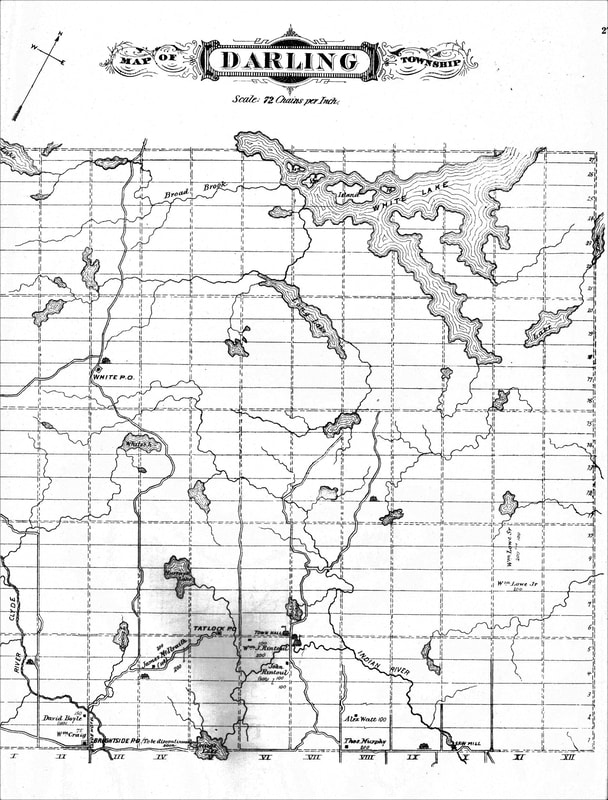

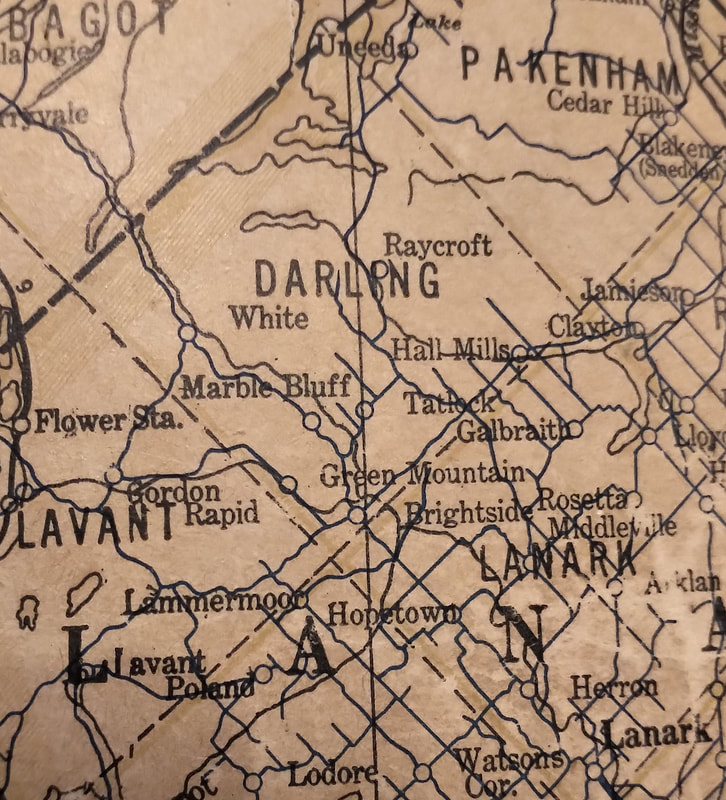

Nestled into the bottom corner of Darling Township, Lanark County, is a small hamlet known as Brightside. It once had a Post Office combined with a store. On the next concession, just west of Brightside, is a place known as Green Mountain. It also had a Post Office from 1912 - 1930. These two Post Offices on Concession One and Two of Darling Township served the surrounding community. Many familiar local names are found in the 1918 Directory below giving clues to who lived in the settlement at the time. A few French families had travelled from Quebec to make this area their home in the mid 1800's. The postal records reveal the names of these families. View the Post Office Directory 1918 here. The Green Mountain community also had three successive schools with the last one being built on Lot 5, Concession 1 around 1946 on land purchased from Antoine Ranger. The Green Mountain schools are included in the Rural Schools: Darling and Lavant Townships published by Archives Lanark. Records for Green Mountain School include many names of children of the French families who settled in the area. St. Declan's Catholic Church and cemetery are located on Concession One of Darling, more commonly known as the French Line Road. Why did these families decide to settle in this location? Why is it called the French Line? A new exhibit at the Middleville and District Museum answers these questios and more. Plan to attend the unveiling of the new French Settlers exhibit on Saturday, August 26th from noon - 4pm.

St Declan’s Catholic Church stands tall and resilient on a hill just west of Brightside in the heart of Lanark Highlands. Generations of parishioners have worshipped and marked important family ceremonies inside its walls. The congregation was established in 1872. The white clapboard structure was built in 1889 on Lot 4 Concession 1 of Darling Township. Father Declan Foley named the Church after the patron Saint Declan. A residence for the priest and a shed to shelter horses during services were built nearby. A cemetery including names of the people who called this area home lies beside the Church. The Middleville and District Museum has a detailed miniature replica of St Declan’s Catholic Church of Brightside as part of its Collection. Visitors are amazed to gaze in through the front door and see the interior of the Church as it was decorated. Even the paintings on the walls are said to be accurate depictions. The pews and altar are built with meticulous care. The model Church will be on display as part of the special exhibit featuring the French Settlement on the French Line in Darling Township in the mid 1800’s. The exhibit will be revealed to the public on Saturday, August 26th, 2023 from noon to 4pm. Be sure to drop by to learn about this settlement that has remained a strong community in the area.

Scarecrows pop up as charming decorations in backyard gardens these days. Historically, they had a very significant role to play. Scarecrows were traditionally used to protect crops from wildlife. Families counted on producing enough food for their family and livestock. Destruction of crops could seriously threaten a family’s survival. If left unchallenged, wildlife could swoop in and feast on the bounty leaving nothing for farmers to feed their family or domesticated animals. When farmers planted, tended and harvested their crops for their family’s food supply, scarecrows served as an insurance policy. The human like features of the scarecrow were intended to fool wildlife into thinking the farmer was still in the field watching over the crop. On Saturday, August 12th, between noon and 4pm, the public is invited to join in the fun of collaborating to create some large scarecrows for the back fence to watch over the Museum’s landscape. Materials will be provided with lots of fun accessories to dress the scarecrows. Come out to the Museum’s grounds to enjoy a glass of lemonade with crafts, games and stories and help us scare some crows! Check out the events page on middlevillemuseum.org or the Museum’s facebook page for more information about this free outdoor event for all ages at the Museum.

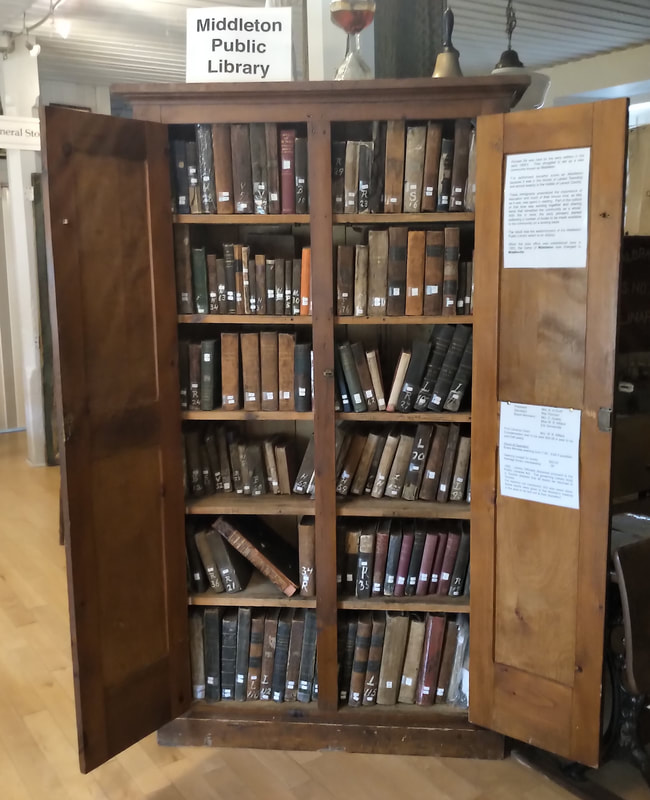

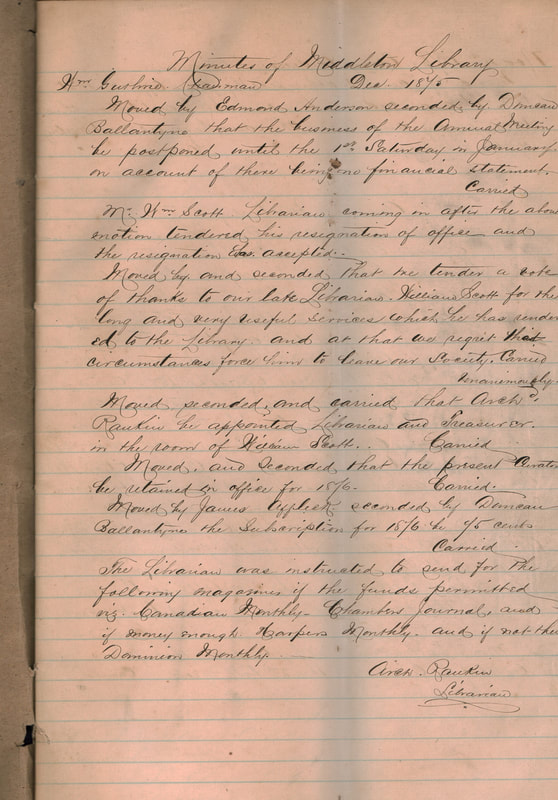

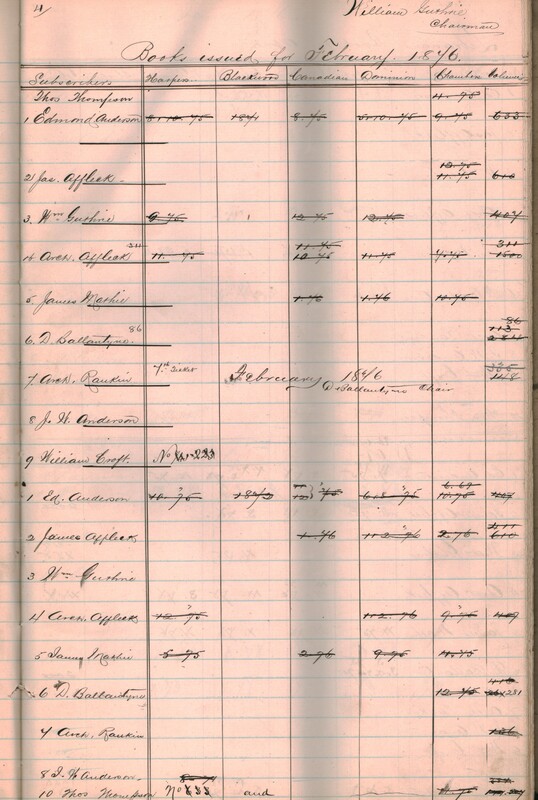

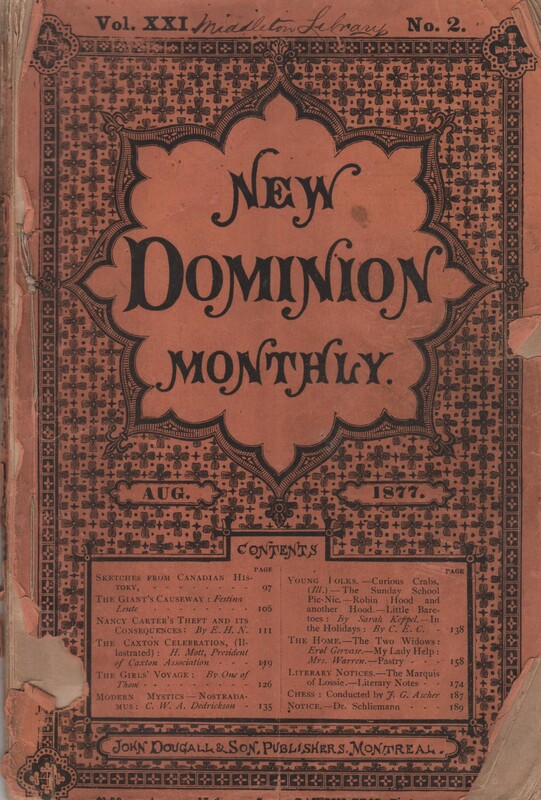

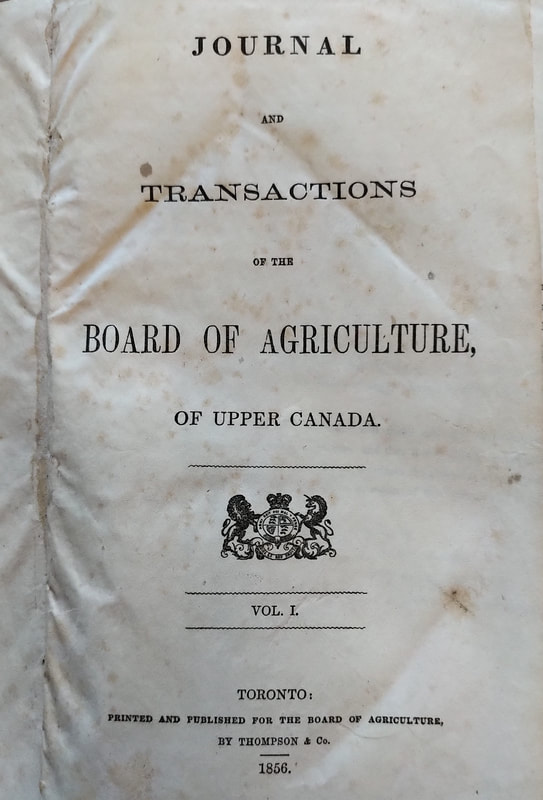

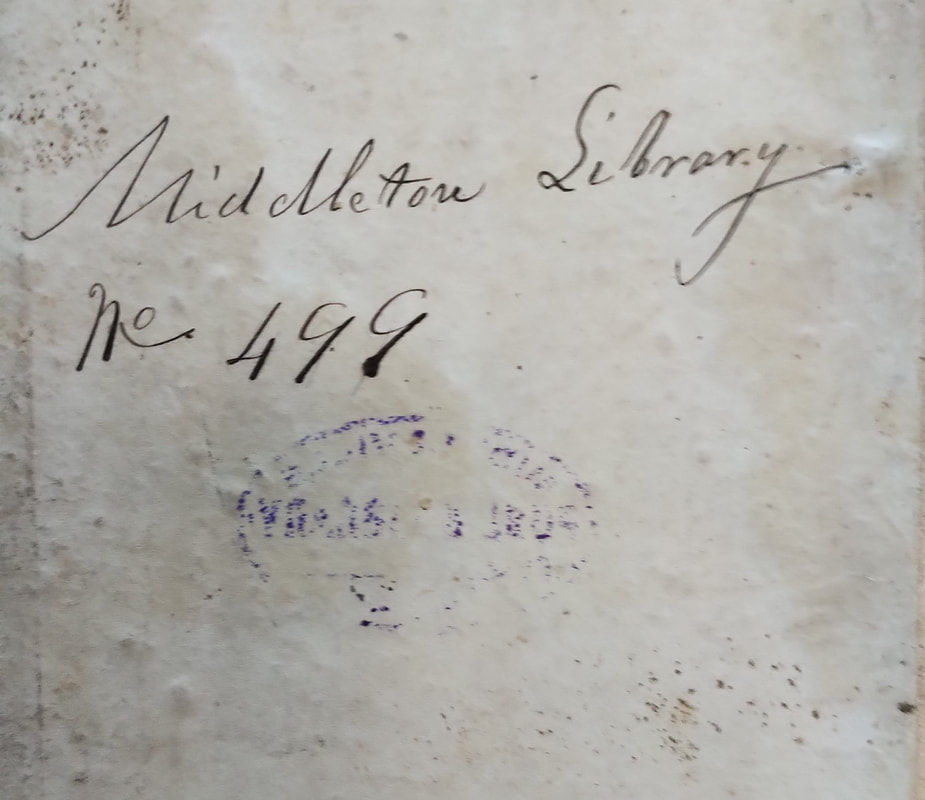

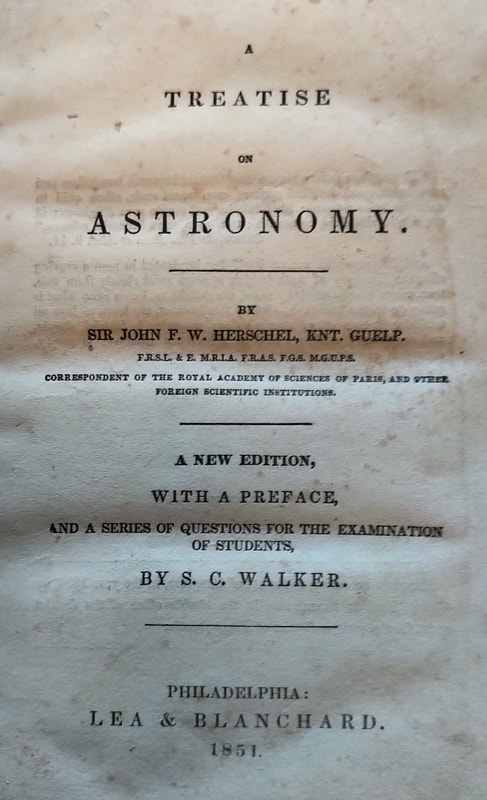

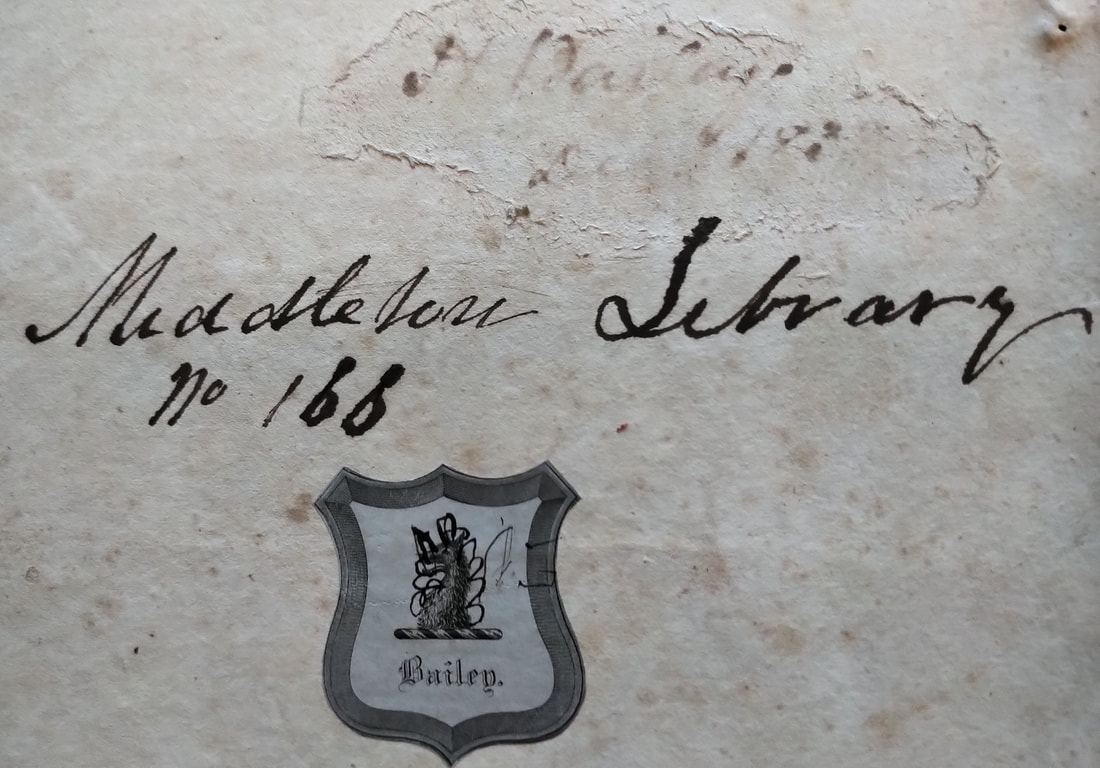

In the case of rain, activities will take place in the large tent as much as possible. Ever wonder what the settlers were reading by candlelight in the long evening hours? Well, the Middleton Library records give some hints. The settlers were often isolated for many days at a time and any chance to share items for mutual benefit was pursued. The early days of community building often included establishing a common source of reading material to both educate and sustain people's interests. Most families had brought a small supply of books along with their other possessions when they emigrated, but these were soon consumed and people sought more titles to read. Pooling their resources was a way to satisfy this need. Many communities established a library in some form or other. In Middleton, a tall, stately cabinet housed the titles collected for borrowing. The Middleton Library cabinet stood in the Township Hall for many years. It now stands in the Middleville and District Museum with its shelves holding books surviving form early days. The titles and subjects of these old books give a glimpse into what the settlers brought with them and their interest in reading material. The subjects include agriculture, religion, geography, history, astronomy, science, politics, memoirs and essays. Many local names appear in the minutes of the meetings and among the lists of borrowers. The books were each given a three digit number and this was recorded beside the name of the person borrowing the book. The number was stroked out when the book was returned. The family names on record as members in 1875 were: Anderson, Affleck, Guthrie, Mathie, Ballantyne, Rankin, Croft and Thompson. Each individual member paid a fee of seventy five cents. This money appeared to go toward library subscriptions for Dominion Monthly, Canadian Monthly and Chambers. The record shows that seven dollars and fifty cents was collected from the membership and the expenses for the subscriptions and postage amounted to seven dollars and thirty-six cents. With the arrival of the Post Office in 1853, the community name of Middleton changed to Middleville. The Library, however, seems to have retained the Middleton name for longer. In the early 1900's, a library bearing the name Middleville seems to have been established according to minutes that have survived. Some books in the Middleton Library cabinet have both names on them so at least some of the books transitioned from one library to the next. Be sure to stop and take a few minutes to look at the books on the shelves of the Middleton Library in the Middleville and District Museum on your next visit. They tell a story of the settler life and their interests.

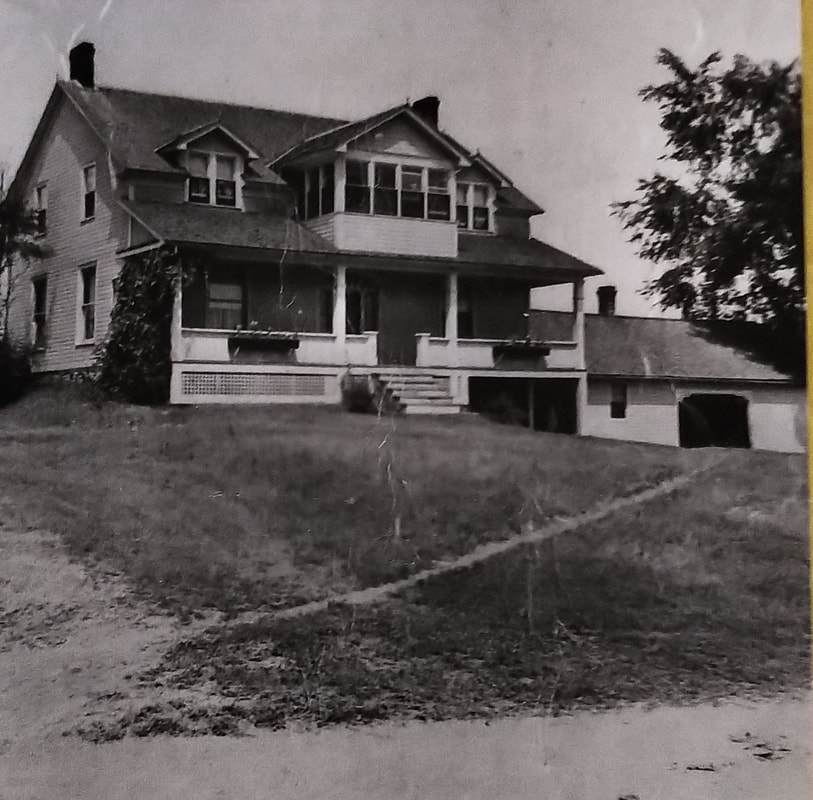

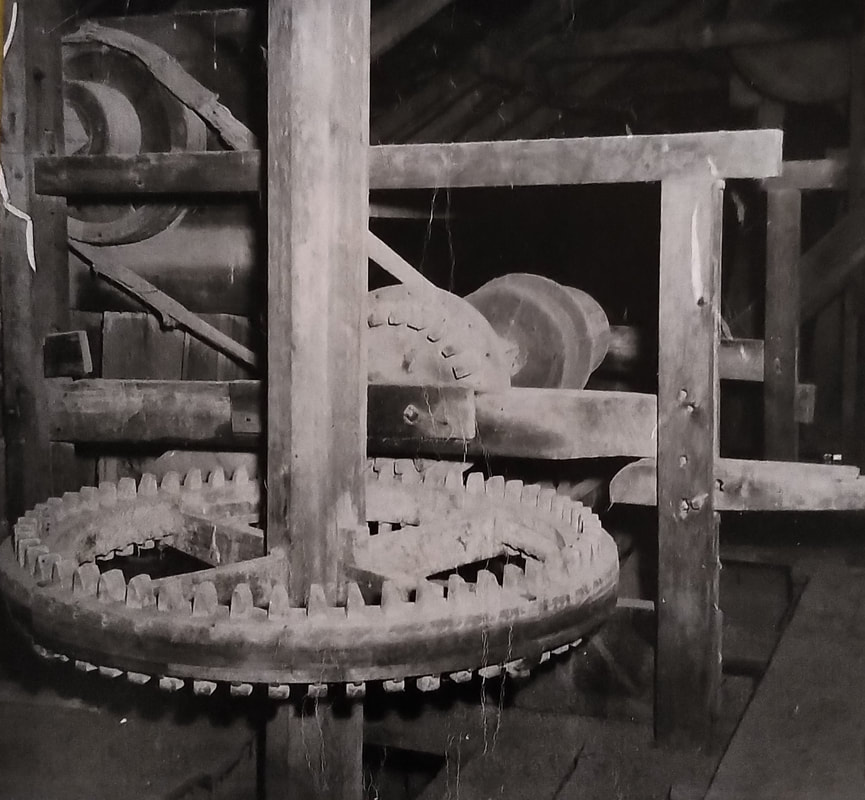

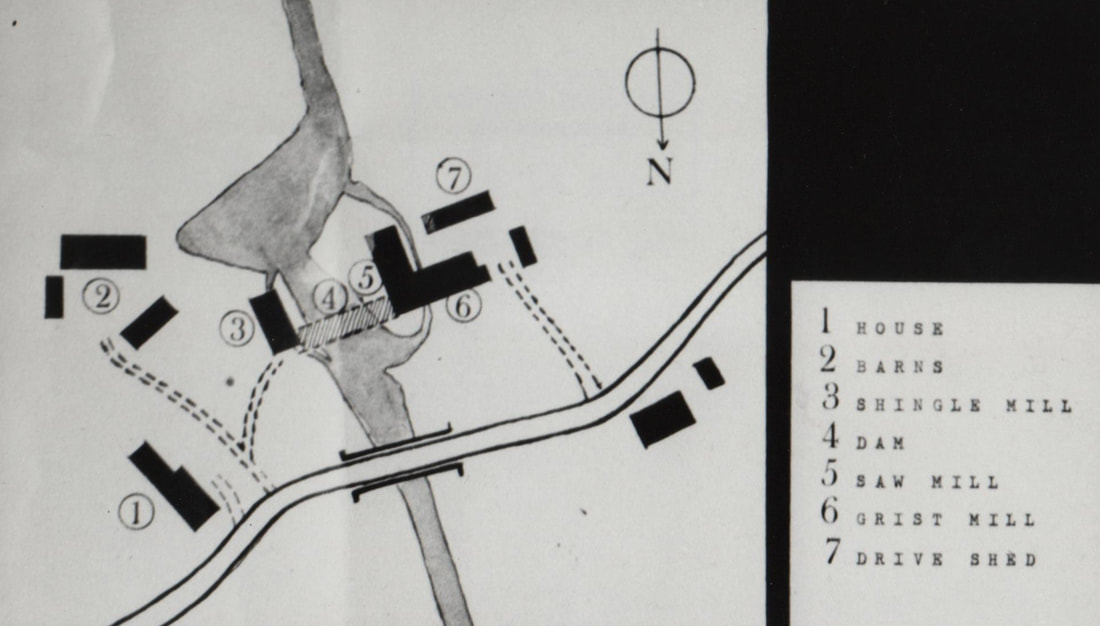

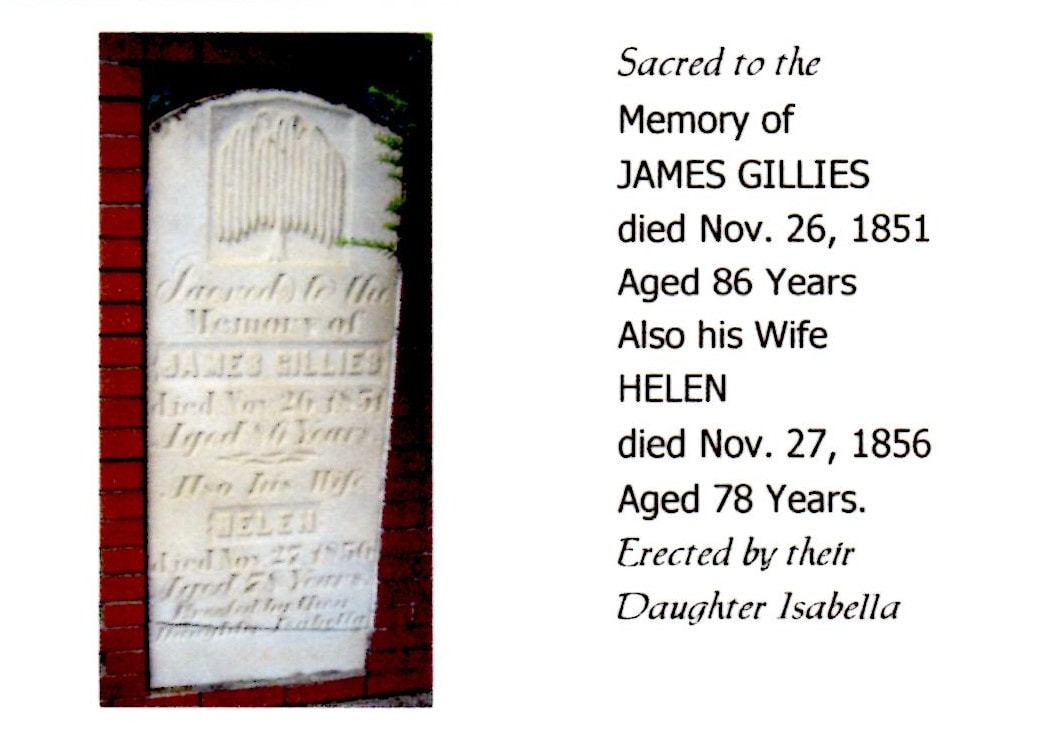

The area now known as Herron Mills was originally settled in the 1820's. Among the early settlers was a weaver, James Gillies. whose family was from Banton, Kilsyth Parish, Stirlingshire. He was married to Helen Stark and they settled their family on Lot 10, 5th Concession. The Clyde River flowed nearby and when their eldest son, John, was old enough to own land himself, he settled on Lot 9, Concession 3 with plans to build a mill on the banks of the river. John married Mary Cullen Bain in 1839 and acquired more land. They built a home overlooking the river and mill site. He built a sawmill in 1840 on the west side of his lot and began sawing logs in 1842. On the other side of the river, he erected grist, oatmeal and carding mills. “Settlers brought their lumber for sawing, their grain for grinding, their wool for combing, carding and spinning and a community grew up”. (J McGill, A Pioneer History of the County of Lanark) In 1871, the Gillies sold their land and home to John Herron. The settlement known until then as Gillies’ Mills became known as Herron Mills The Herrons enlarged the home and operated a post office from it. There were other buildings at Herron Mills, as well. There was a tannery operated between the Herron house and barn. There were houses built where mill managers lived. A log school was built on the east side of Concession 3 and opened in 1846. The school, SS # 5, is now a private dwelling. The history of the school can be found the Museum in the school histories display.

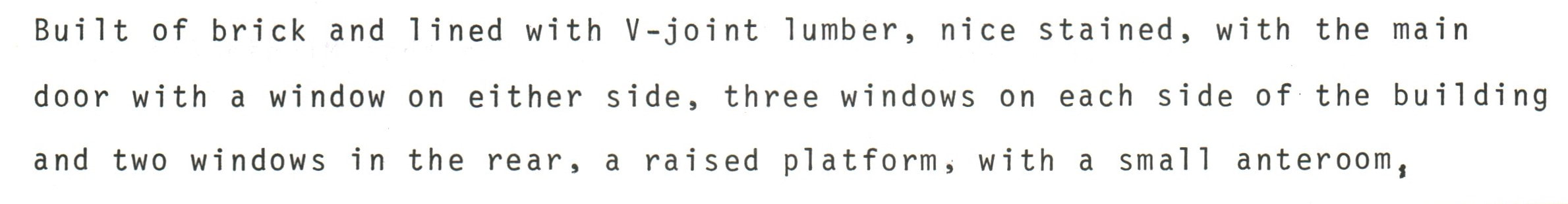

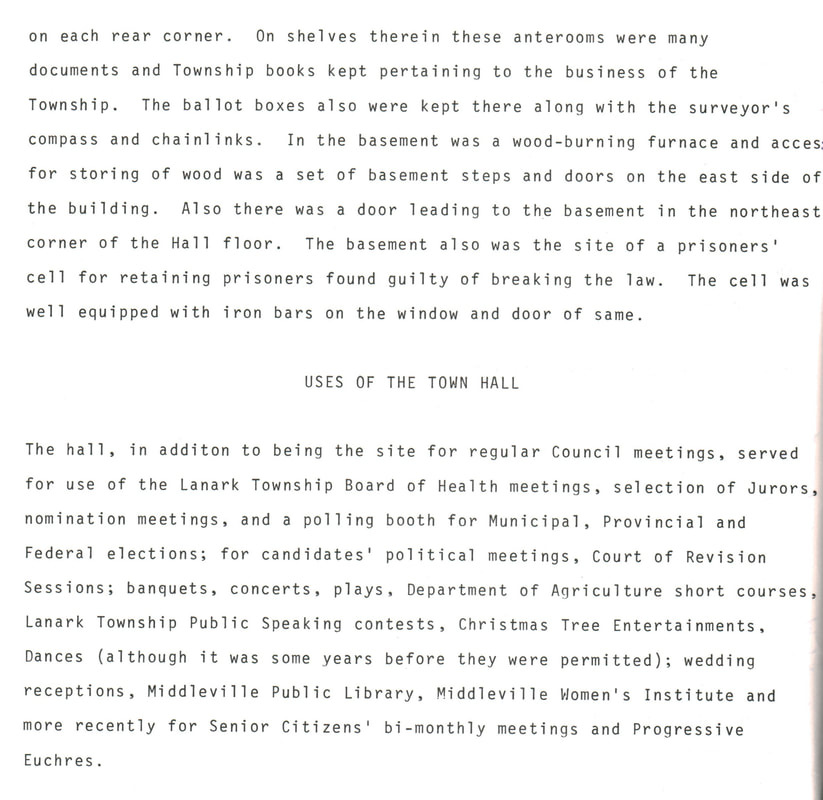

The Museum has a display that focuses on Herron Mills with many photographs and chronicles of its history. Be sure to have a look at it when you visit. Records of an inaugural meeting in 1854 referred to the 'Council of Lanark Township' for the first time. After the incorporation of the Village of Lanark as a separate municipality in 1862, the government of Lanark Township was seated in the central location of Middleville. The council met in the newly constructed Middleville stone schoolhouse from the middle of 1862 to the end of 1863. During 1863, a small building known locally as the 'Mechanic’s Institute' was purchased and plans for renovations were detailed. This log building was situated in the area of the present day Fire Hall. It served as the Township Hall until the current one was opened. In early 1899, a deal to purchase land from Rachel Lawson involved negotiations for a land swap giving her land on the other side of her property and a new Township Hall was built on its current site. It was completed and opened later that year. By-law No. 167 was registered in February of 1899 to provide for the sum of $1200 being raised for the construction of the new township hall. The councillors at the time were John Ryan, James Matthie, James Affleck and Alexander B. Yuill. William Rankin had the contract to 'fit up and finish' the new hall. The following description of the features of the LanarkTownship Hall indicate how it was designed at the time it was first built. This description is taken from the writing of Agnes Yuill as compiled by N. Tyres for a booklet publication in 1984. The length of the Hall was increased by the depth of the platform and later a kitchen was added in the basement underneath the platform. The kitchen was equipped with a wood stove, shelves to hold food and tables to create a work space. These were considered modern accomplishments in their time. The Middleville and District Museum has many original documents that bear witness to the history of the village. The Lanark Township Hall certainly has a place in that history.

A few years ago, the Middleville and District Museum volunteers were intrigued by the idea of bringing a special show to the Museum. It sounded like an interesting idea. A little research revealed that the shows were performed by a renowned theatre troupe with a Governor General’s award nomination to its credit. In fact, Live History is a company of actors that performs internationally having done shows in 7 different countries. The concept is simple. Take a local story in a community and have script writers dramatize it for a group of actors who perform it for an audience. There are a few distinguishing features of these shows. The travelling troupe visits the community venue and the actors themselves join the audience for an afternoon tea. The audience soon realizes that there are some mystery guests in their midst who seem a little confused or out of place. The audience is encouraged to help these disoriented guests by answering some questions and solving some curious quandaries. Afterall, these strangers are in an unfamiliar place and need some assistance. The show unfolds in a relaxed atmosphere as the guests try to figure out what has brought these mysterious characters into their midst. The tea, coffee and sweet treats are consumed by the guests while they watch the story unravel and be revealed in front of their eyes. The show is designed to appeal both to those who enjoy actively solving puzzles and those who prefer to watch quietly as the show develops. After hosting two successful sold out shows last season, the Museum volunteers were eager to invite Live History back to offer another new, local story. The Museum volunteers are certain this year’s audiences will enjoy the shows, as well.  Live History presents a full range of show offerings and works with local communities to customize a performance that fits their unique venue. Visit the Live History website to learn more about this renowned theatrical organization |

AuthorThis journal is written, researched, and maintained by the volunteers of the Middleville Museum. |